13 novembre 2024

BENEATH THE SURFACE: WHAT MEDIEVAL MOBILITY REVEALS ABOUT INTERGENERATIONAL WEALTH TRANSMISSION

Marianna Belloc Roberto Galbiati Francesco Drago

(synthesis; full article 12 Nov 2024

https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/beneath-surface-what-medieval-mobility-reveals-about-intergenerational-wealth)

Abstract: The Middle Ages are widely understood as an era of economic immobility. This column uncovers a more nuanced picture. Wealth transmission in late medieval Florence was characterised by both mobility and persistence. While there was a notable degree of social mobility across adjacent generations, privilege tended to persist over longer horizons. Social and political networks played a significant role in generating such persistence, with families embedded in marriage networks and political institutions securing prosperity and status. The findings provide a historical perspective on the dynamics of wealth transmission.

Keywords: Economic History, poverty, income inequality, Middle Ages, intergenerational wealth, Italy.

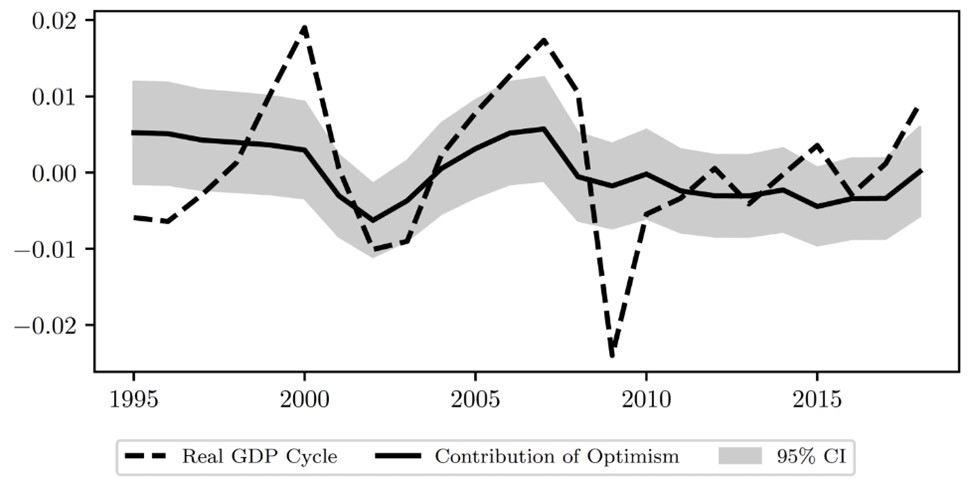

It is a widespread belief that the Middle Ages were characterised by an immobile society in which socioeconomic status was transmitted inexorably from fathers to sons, in a context of little opportunity to climb the social ladder, no system of public education, and inherited professions. This idea is consistent with empirical results by Mocetti and Barone (2016) documenting that the top income earners in contemporary Florence descend from the wealthiest families of the 15th century. Our study (Belloc et al. 2024a) uncovers a more nuanced picture. Quite surprisingly, we find a relatively high degree of short-run mobility in late medieval Florence, not so distant from that of modern Western societies. But this result masks a deep-rooted persistence of economic status across generations over the longer run. These findings not only refine our knowledge of the historical processes of intergenerational wealth transmission; they also offer valuable insights into broader underlying mechanisms that continue to influence inequality in modern societies.

In the paper, we exploit a large dataset that combines four subsequent wealth assessments – 1403, 1427, 1457, and 1480 – to provide detailed information on the universe of Florentine households spanning nearly a century. 1 The richness of the dataset allows us to investigate the transmission mechanisms within direct (parent-son) family ties as well as broader kinship networks and to study the underlying data generating process.

We begin by evaluating the extent of short-term social mobility through the estimation of two-generation models. Our results, obtained by regressing children’s wealth outcomes on those of their parents, suggest that Florentine society was relatively mobile in the short run over the considered time span, with estimated rank-rank correlation coefficients between 0.4 and 0.5 comparable to the correlation coefficients found in modern cities (two-generation coefficients for 20th-century Sweden, estimated by Adermon et al. 2018, go from 0.3 to 0.4 depending on the specification). These findings are consistent with other studies documenting a fair amount of socioeconomic mobility in medieval urban centres (Padgett 2010).

We then consider intergenerational wealth transmission across multiple generations. The adoption of the two-generation correlation coefficients to make inferences on the long run is likely to systematically overestimate the degree of mobility. Indeed, as discussed by several authors (Braun and Stuhler 2018), these extrapolations are likely to neglect important factors underlying the actual wealth transmission process. This is confirmed by our data when we link children directly to grandfathers and find substantially larger numbers (meaning lower mobility) than those inferred from standard iteration techniques.

To explain these findings, we evaluate two potential explanations. The first is the ‘grandparental effects model’, according to which grandparents pass their status to grandchildren via direct transmission of wealth, resources, or skills. The second is the ‘latent factor model’, which attributes wealth persistence to an unobserved factor that is passed down across generations at a high rate and that correlates to wealth without necessarily involving direct contact. In both models, mobility between two generations can be high. But in the long run, with the contribution of either the grandparents (in the first model) or the latent factor (in the second model), persistence of the economic status is empirically generated.

We run a series of exercises to discriminate between the two possible data processes, and our results lend support to the latent factor model. For example, we demonstrate that even in cases with little likelihood of direct interaction between (great-) grandparents and (great-) grandchildren (due to age difference or other factors), wealth outcomes of the younger generation are still strongly correlated with those of the elder generation. This suggests that wealth transmission is mediated by factors other than direct inheritance or financial transfers, providing evidence for the role of a latent factor.

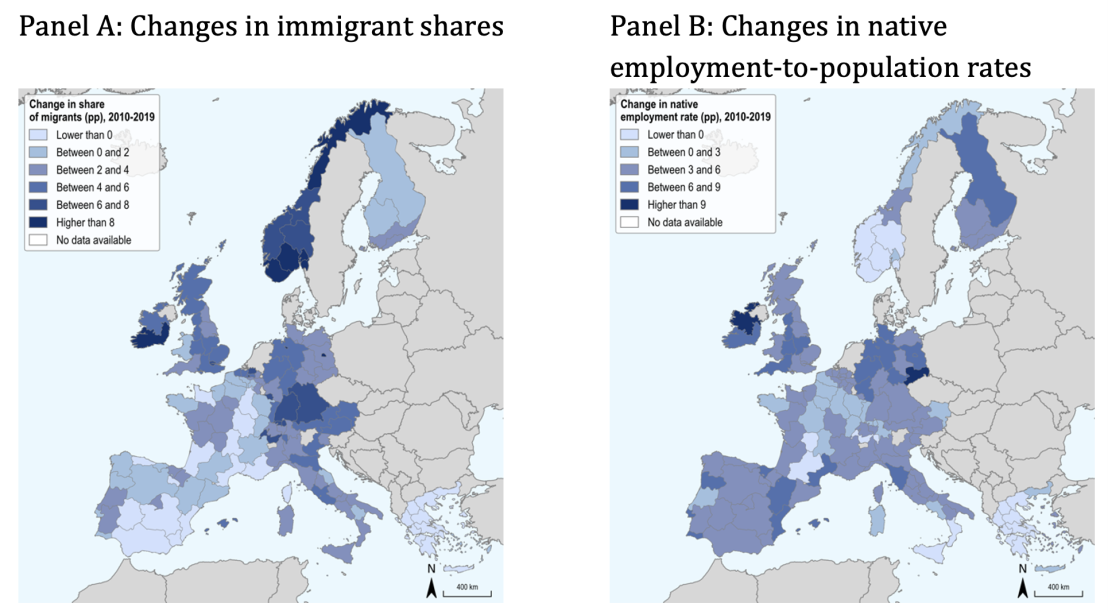

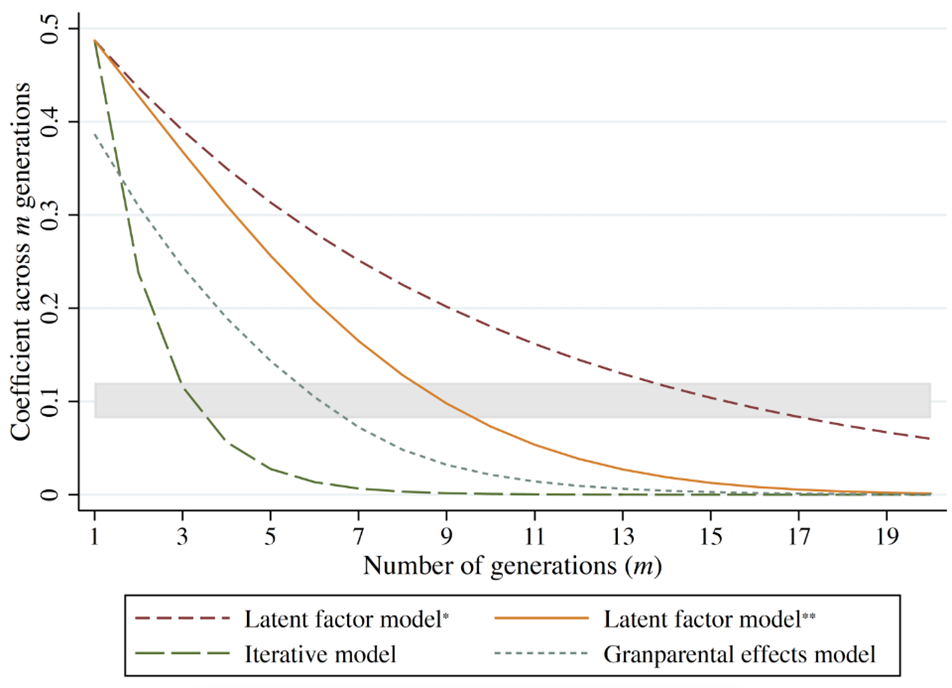

We also discuss how our findings can explain the very long-term persistence of economic status, documented by Barone and Mocetti (2021), which links Florentine families’ wealth from the 15th century (1427) to economic status in the present day (2011). To this purpose, we simulate wealth transmission over 600 years by employing our previously estimated coefficients. Figure 1 depicts the horse race across alternative approaches. While the latent factor model run with our data predicts a slightly lower degree of long-term wealth persistence than that found by Barone and Mocetti, our findings confirm that wealth status can persist across many generations and that this is true even in the presence of a discrete amount of mobility in the short run (two-generation model). This conclusion further supports the latent factor model’s explanatory power of very long-run trends.

Figure 1 Prediction of wealth status transmission from alternative models

Notes: The picture shows the predicted correlation coefficients across m-generations from alternative models: latent factor model, iterative model, and grandparental effects model. The shaded area depicts the range of the estimated coefficient across 19 generations by Barone and Mocetti (2021). * Predictions are obtained assuming a constant heritability parameter. ** Predictions are obtained assuming that the heritability parameter declines by 1% every generation.

Finally, we explore mechanisms that could explain wealth status persistence and identify possible latent factors. In particular, we investigate the potential role of marriage networks and political participation. As regards the former, we complement our data with information on Florentine marriage networks (Padgett 2010) and find that families with higher ‘structural cohesion’ (measured by the number of marriage links to be severed to disconnect a family from the network) tend to experience greater wealth persistence. In other words, families that were more deeply embedded in the social fabric of Florence through marriage links were better able to maintain their economic status across generations. As for the latter, we employ data on political participation (the Tratte records) from Herlihy et al. (2002). We determine that Florentine citizens who held political office were more likely to belong to families with enduring wealth status, suggesting that access to political power helped reinforce economic advantage for wealthy elites. This connection between wealth and political influence underscores the importance of social capital in the transmission of wealth.

Our study adds to the growing body of literature on the intergenerational transmission of economic status, particularly in historical contexts. While much of the recent research focuses on contemporary societies (Pica et al. 2018, Polo et al. 2019, Porter et al. 2018), we show that similar mechanisms of wealth transmission were operating centuries ago. Our findings are consistent with other studies that have examined long-term wealth persistence, such as those by Ager et al. (2021) and Clark (2014), which also found that wealth status can persist for many generations, driven by latent factors rather than direct inheritance alone. By linking wealth data across multiple generations in premodern Florence, we provide insights into the broader forces that shape economic mobility. From the simple estimation of two-adjacent generation models, we are unable to make inferences on economic status persistence over the long run. We also highlight the importance of social networks and political engagement in maintaining wealth, even during an era marked by significant social and political change (Belloc et al. 2024b, Goldthwaite 2009, Najemy 2006). The use of a dataset spanning over four generations offers a rare opportunity to analyse long-run economic mobility in a historical setting, contributing to a more nuanced understanding of how wealth is transmitted over time.

In conclusion, we find that wealth transmission in late medieval Florence was characterised by both mobility and persistence. This is not an oxymoron. While there was a notable degree of social mobility across two adjacent generations, wealth status tended to persist over longer horizons, driven by latent factors transmitted across multiple, possibly non-adjacent generations. Social and political networks played a significant role in generating such persistence, with families embedded in marriage networks and political institutions better able to secure their wealth and status. Our findings provide a historical perspective on the long-term dynamics of wealth transmission and offer lessons for understanding contemporary patterns of economic mobility.

7 novembre 2024

DOUBLE PRICING OF GREENHOUSE GAS EMISSIONS IN SHIPPING: COMPETITIVENESS, CLIMATE, AND WHAT TO DO ABOUT IT

Goran Dominioni Christy Ann Petit

(synthesis; full article 06/11/2024https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/double-pricing-greenhouse-gas-emissions-shipping-competitiveness-climate-and-what-do)

Abstract: International shipping faces significant challenges as emissions trading schemes expand, potentially leading to overlapping greenhouse gas pricing mechanisms. Concerns are rising among shipping companies that double pricing could reduce their competitiveness and raise costs. This column identifies three potential scenarios in which emissions from international shipping could become subject to multiple GHG pricing instruments, and suggests that one way to avoid double pricing would be to implement a crediting mechanism whereby payments made under one instrument are credited under the other.

Keywords: emission trading, shipping, climate change, international trade

International shipping is the backbone of the global economy, accounting for about 80% of international trade (Vuillemey 2020). As the EU extends the application of its Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) to international shipping and the International Maritime Organization (IMO) works on the adoption of a greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) pricing mechanism for the same sector, the prospect of GHG emissions from international shipping being subject to multiple pricing instruments is becoming more likely. While it is common for pricing instruments to overlap in other sectors (Agnolucci et al. 2023), some shipping companies have expressed concerns about the double pricing of GHG emissions, as this may reduce their profits and competitiveness. Similarly, as higher shipping costs can result in higher prices of transported goods (Ostry et al. 2022), some countries are worried about its potential to reduce trade opportunities, and that it may result in negative impacts in terms of GDP and food security.

In a recent paper (Dominioni and Petit 2024), we identify three potential scenarios in which emissions from international shipping could become subject to multiple GHG pricing instruments:

- A first scenario is two or more jurisdictions implementing overlapping GHG pricing instruments for international shipping at the sub-global level, both targeting downstream emissions (i.e. emissions from vessels). Besides the extension of the EU ETS to international shipping, various jurisdictions are considering the implementation of a GHG pricing instrument for this sector, such as the US International Maritime Pollution Accountability Act of 2023.

- A second scenario is the IMO implementing a GHG pricing instrument which overlaps with another sub-global GHG pricing instrument targeting downstream emissions, such as the EU ETS or a pricing instrument from another jurisdiction.

- Lastly, a third scenario is the IMO or another jurisdiction implementing a GHG pricing mechanism that also covers upstream emissions, such as emissions released in the production of liquefied natural gas used as a bunker fuel.

Should double pricing be avoided at all costs?

GHG pricing and other GHG policies for shipping may impact the competitiveness of shipping companies and countries, even though research indicates that these impacts tend to be small on average (Cariou et al. 2023, Rojon et al. 2021). Double pricing could entail a further reduction in competitiveness for shipping companies, as a result of needing to comply with two or more GHG mechanisms simultaneously, and a further reduction in trade opportunities for some countries. However, the case for avoiding double pricing rests on a balancing of interests and on how these instruments are implemented in practice.

Higher carbon prices normally result in greater emissions abatements (Känzig and Konradt 2023). If the IMO implements weak GHG policies, additional climate policies – including GHG pricing – from the EU and other countries would be essential to ensure a fast decarbonisation of the shipping sector. Indeed, research suggests that marginal abatement costs to reach net-zero carbon emissions by 2050 are around $300 per tonne of carbon (Longva et al. 2024).

In addition, some potential negative effects of double pricing may be mitigated through instrument design. For instance, World Bank research indicates that using a share of carbon revenues from shipping to improve port efficiency or support the deployment of zero-carbon bunker fuels can reduce the potential negative impacts of GHG pricing on vulnerable countries and shipping companies (Dominioni and Englert 2022). The cost incurred by companies in complying with multiple GHG pricing instruments can also be reduced through the harmonization of those instruments (e.g. on verification and reporting).

Thus, overall, the case against double pricing rests on contingent factors, many of which are in the hands of policymakers working on these policies.

What could be done to avoid double pricing?

If policymakers decide to avoid the double pricing of GHG emissions from shipping, one way to do so would be to implement a crediting mechanism, whereby payments made under one instrument are credited (i.e. discounted) under the other. That is, a shipping company would pay a price on its GHG emissions under one instrument, and this payment would be subtracted from the payment of another instrument.

Implementing a crediting mechanism such as the one discussed above requires establishing some level of comparability of different GHG pricing instruments. This may be relatively easy for some GHG instruments, but more complicated for more complex ones (Dominioni and Esty 2023). Luckily, there is a growing body of research concerned with developing methodologies to compare different types of GHG pricing instruments (Agnolucci et al. 2023). This knowledge could be harnessed in the maritime transport sector to avoid double pricing.

This knowledge can also help the IMO to implement a GHG pricing instrument for international shipping that is considered at least as ‘equivalent’ to the EU ETS. Currently, the EU plans to review the extension of the EU ETS to international shipping in 2027, taking into account the GHG pricing mechanism adopted by the IMO in the meantime. An IMO GHG price equivalent to the EU ETS may prevent a further expansion of the latter (currently the EU ETS covers only a fraction of GHG emissions released in transporting goods from and to the EU) and, potentially, even its retraction from shipping. It is worth noting that, during an event in October 2024, the European Commission, represented by a senior official from the directorate-general for Mobility and Transport (DG Move), was reported as reassuring that the EU stands ready to take into account the forthcoming IMO global instrument and adapt the EU ETS in line with the ETS Directive review clause to “avoid any significant double burden”. (Lowry 2024).

Who can help shipping policymakers to avoid double pricing?

Much of the knowledge on establishing equivalence between GHG policies – including carbon pricing – has been created in the context of the implementation of border carbon adjustment mechanisms, i.e. charges on the GHG emissions embedded in internationally traded products.

In our paper, we identify different pathways through which regulatory cooperation can take place. Various countries that have or are planning to implement border carbon adjustment mechanisms, as well as institutions like the OECD, the IMF, the World Bank, and the WTO, are developing significant knowledge on comparing policies that put a price on carbon (e.g. Agnolucci et al. 2023, IMF 2019, OECD 2023). If double pricing in shipping is to be avoided, these is a case for this knowledge to be shared with IMO policymakers and other teams that work in jurisdictions which implemented or are implementing domestic GHG pricing mechanism for international shipping.

Border carbon adjustments mechanism can also include crediting mechanisms similar to those that may be implemented to avoid double pricing in international shipping. For instance, the EU Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) credits for carbon pricing instruments implemented in countries that export to the EU (European Parliament and Council of the European Union 2023). Policymakers working on border carbon adjustment mechanism could also contribute their expertise on how to design crediting mechanisms to the IMO and within sub-global discussions on the implementation of GHG pricing for international shipping.

On this basis, we argued in favour of regulatory cooperation between the IMO, IMF, OECD, World Bank and the WTO, as well as policymakers working on shipping decarbonisation and border carbon adjustment mechanisms at the EU or national level.

4 settembre 2024

THE MACROECONOMICS OF NARRATIVES

(synthesis; full article 30/08/2024 https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/macroeconomics-narratives)

Abstract: The idea of an episode of negative sentiment causing poor economic performance has gained prominence in the press and drawn attention from policymakers struggling to read contradictory macroeconomic signals. This column applies natural language-processing tools to assess the importance of narratives for the US business cycle. The analysis suggests that contagious narratives are an important driving force in the business cycle, but not all narratives are equal in their potential to shape the economy, and the fate of a given narrative may rest heavily on its (intended or accidental) confluence with other narratives or economic events.

Keywords: politics and economy, macroeconomic policy, narratives, business cycle.

Can a negative mood tank the economy? Recently, discussion about a ‘vibe-cession’, or an episode of negative sentiment that might cause poor economic performance, has gained prominence in the financial press (Scanlon 2022a, 2022b, Keynes 2023) and drawn serious attention from policymakers struggling to read contradictory macroeconomic signals (Federal Open Market Committee 2024).

The idea that emotional states may affect the economy has a long intellectual history. John Maynard Keynes regrettably missed his chance to coin ‘vibe-cession’, but he wrote extensively about how peoples’ instinctive ‘animal spirits’ drove crashes and recoveries. Taking this idea one step further, economist Robert Shiller has advocated for a more detailed study of economic narratives, or contagious stories that shape how individuals view the economy and make decisions. Viral narratives could be the missing link between emotions and economic fluctuations. But, as economic modellers, we currently lack effective tools to measure these narratives, model their possible impacts on the economy, and quantify their contribution toward economic events.

Our recent research (Flynn and Sastry 2024) makes a first attempt to understand the macroeconomic consequences of narratives. We introduce new tools for measuring and quantifying economic narratives and use these tools to assess narratives’ importance for the US business cycle.

Measuring narratives using natural language processing

To measure narratives, we use resources not available to Keynes: large textual databases of what economic decisionmakers are saying and natural language-processing tools that can translate this text into hard data. Specifically, we study the text of US public firms’ SEC Form 10-K, a regulatory filing in which managers share “perspectives on [their] business results and what is driving them” (US Securities and Exchange Commission 2011), and their earnings report conference calls. We process these data using three methods designed to capture different facets of firms’ narratives: (i) a sentiment analysis; (ii) a textual similarity analysis that looks for connections to the “perennial economic narratives” that Shiller (2020) identifies as particularly influential in US history; and (iii) a fully algorithmic ‘latent dirichlet allocation’ model that looks for any repeating patterns in firms’ language. Using these methods, we obtain quantitative proxies for the narratives that firms use to explain their business outlook over time – for example, firms’ general optimism about the future, their excitement about artificial intelligence trends, or their adoption of new digital marketing techniques.

Narratives shape firms’ decisions and spread contagiously

In our data, we find that firms with more optimistic narratives tend to accelerate hiring and capital investment. This effect is above and beyond what would be predicted by firms’ productivity or recent financial success. Strikingly, firms with optimistic narratives do not see higher stock returns or profitability in the future and also make over-optimistic forecasts to investors. That is, firms’ optimistic and pessimistic narratives bear the hallmarks of Keynes’ ‘animal spirits’: forces that compel managers to expand or contract their business but do not predict future fundamentals.

We next find that narratives spread contagiously. That is, firms are more likely to adopt the narratives held by their peers, both at the aggregate level and within their industries. The narratives held by larger firms have an especially pronounced effect. Thus, consistent with Shiller’s hypothesis, narratives can spread like a virus: once some take a gloomy outlook in their reports or earnings calls, others follow suit.

Narratives drive about 20% of the business cycle

To interpret these results, and leverage them for quantification and prediction, we develop a macroeconomic model in which contagious narratives spread between firms. Because narratives are contagious, they naturally draw out economic fluctuations: even a transient, one-time shock to the economy can have long-lasting effects because a negative mood infects the population and holds back business activity. Sufficiently contagious narratives that cross a virality threshold can induce a phenomenon that we call narrative hysteresis, in which one-time shocks can move the economy into stable, self-fulfilling periods of optimism or pessimism. In these scenarios, there is a powerful positive feedback loop: economic performance feeds a narrative that reinforces the economic performance. These findings underscore the importance of measurement to discipline exactly how much narratives affect the economy.

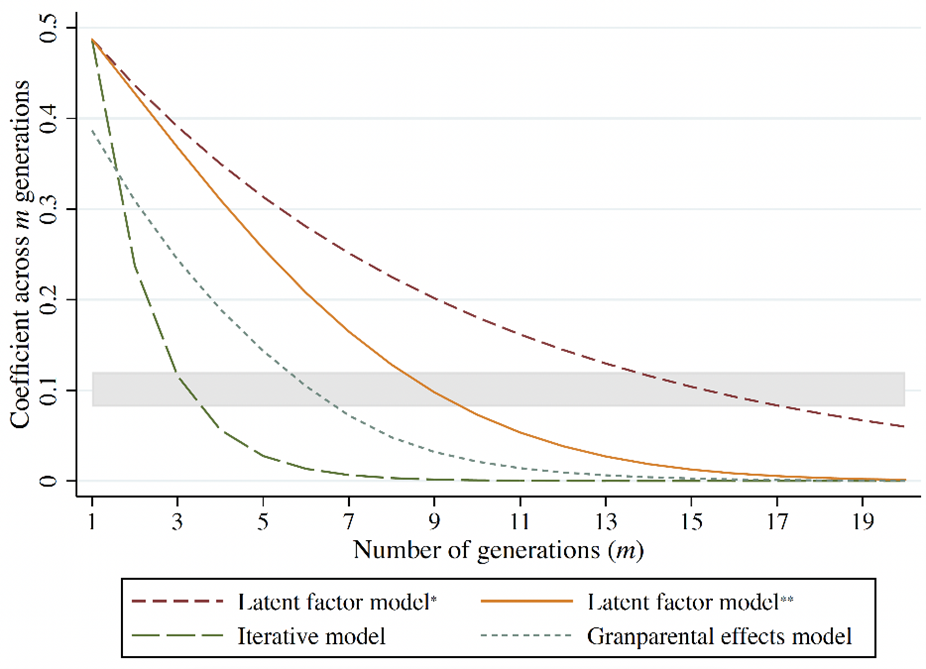

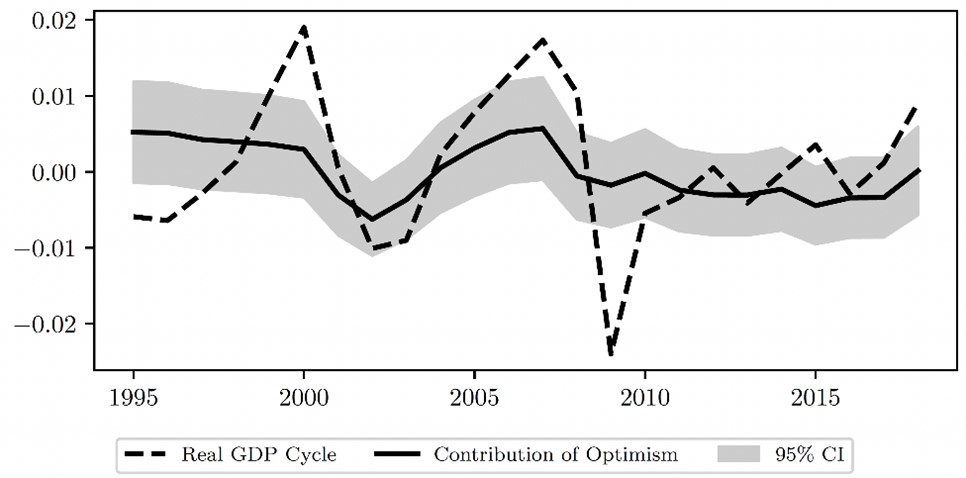

Figure 1

Note: The dashed line plots the US business cycle from 1995 to 2018. The solid line, based on our analysis, is the contribution of contagious narratives toward business-cycle fluctuations. The shaded area is a 95% confidence interval based on statistical uncertainty in our estimates.

How strong are the narratives driving the US economy? Combining our empirical results with our theoretical model, we estimate that narratives explain about 20% of the US business cycle since 1995 (Figure 1). In particular, we estimate that narratives explain about 32% of the early 2000s recession and 18% of the Great Recession. This is consistent with the idea that contagious stories of technological optimism fuelled the 1990s Dot-Com Bubble and mid-2000s Housing Bubble, while contagious stories of collapse and despair led to the corresponding crashes. Our analysis, building up from the microeconomic measurements of firms’ narratives and decisions, allows us to quantify these forces.

When can economic narratives ‘go viral’?

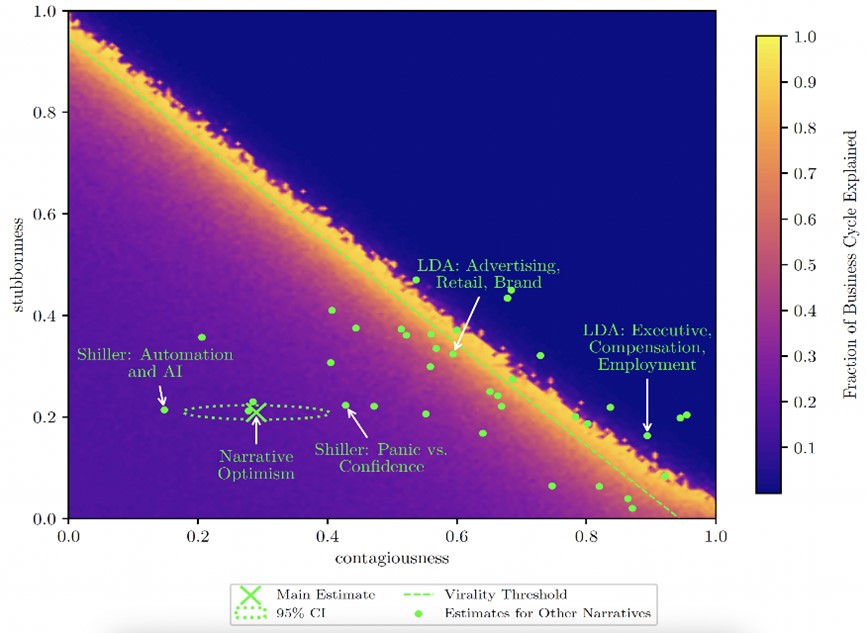

Our findings suggest that optimistic narratives generate business cycles, but do not truly ‘go viral’ and generate narrative hysteresis. Figure 2 visualises this by showing how much narratives might have affected output if they were counterfactually more prone to virality. We focus on two key parameters disciplined by our measurement: the ‘stubbornness’ with which firms maintain existing narratives, and the ‘contagiousness’ with which narratives spread. Our main estimate, denoted with a large “x”, is far from the virality threshold we derive theoretically (denoted by a dashed line). If the narrative were associated with greater stubbornness or contagiousness, then narrative dynamics would be considerably more violent – potentially explaining almost all of the business cycle, in the most extreme calibrations.

Figure 2

Note: This figure illustrates the tendency of business-cycle narratives toward virality. The horizontal and vertical axis respectively denote measurable contagiousness (how much a narrative spreads) and stubbornness (how much proponents stick to their narrative). The “x” corresponds to our measurement for the main narrative affecting US business cycles, and the dots correspond to our measurements for more granular narratives. Selected narratives are labelled. The shading denotes how much of the business cycle the narrative explains for a given level of contagiousness and stubbornness. The dashed line denotes the theoretical virality threshold that determines whether narrative hysteresis is possible.

Does that mean that all economic narratives lead tranquil lives? Not necessarily. In further analysis, we study the spread and effect of more granular narratives picked up by our other natural language-processing analysis. These narratives are associated with higher stubbornness and virality and are therefore more prone to ‘going viral’ (as denoted by the small circles). Viewed from afar, the narratives in the US economy form a constellation whose stable behaviour on average belies more violent individual fluctuations. This is consistent with the idea that ‘vibe-cessions’ are slow-moving, but more specific fears and fads move quickly.

Policymaking in the narrative economy

Our analysis suggests that contagious narratives are an important driving force in the business cycle. But it also qualifies this conclusion in important ways. Not all narratives are equal in their potential to shape the economy, and the fate of a given narrative may rest heavily on its (intended or accidental) confluence with other narratives or economic events.

How should policymakers act in a narrative-driven economy? Our analysis has at least three major conclusions, which also suggest future directions for both academic and policy research.

First, what people say about their economic situation is highly informative about both individual attitudes and broader trends in the economy. Public regulatory filings and earnings calls already contain considerable information. Both policymakers and researchers can use improved machine-learning algorithms and data-processing tools to analyse this information. There are also possible implications for how researchers and governments collect information. The same data-science advancements have increased the value of novel surveys that allow households or businesses to explain the ‘why’ behind their attitudes and decisions (e.g. Wolfhart et al. 2021).

Second, some narratives are more influential and contagious than others. It is therefore important to combine descriptive studies measuring narratives with empirical analysis of their effects on decisions and their spread throughout populations.

Third, the narratives introduced by policymakers could be potentially very impactful. We know relatively little about what makes a policy narrative into a great story that spreads contagiously and affects the economy on its own. Understanding these dynamics is an important area for future research.

7 agosto 2024

POLITICAL EXPRESSION OF ACADEMICS ON SOCIAL MEDIA

(synthesis; full article 30 july 2024 Vox Eu CEPR https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/political-expression-academics-social-media)

Abstract: Social media platforms allow for immediate and widespread dissemination of scientific discourse. However, social media may distort public perceptions of academia through two channels: the set of topics being discussed and the style of communication. This column uses a global dataset of 100,000 scholars to study the content, tone, and focus of their social media communications. It finds systematic differences in the views expressed by academics and the general public, in both the topics and the tone of discussion. There are also clear differences between academics, depending on their gender, field, country of affiliation, and university ranking.

Keywords: politics and economy, social media, trust in scientists, academy.

Social media platforms may be important marketplaces for the exchange and dissemination of ideas, where academics and researchers hold significant roles as knowledge producers and influencers (Cagé et al., 2022, Gentzkow and Shapiro 2011). Policymakers may actively scout these platforms for policy insights or ideas, while journalists increasingly rely on digital sources like Twitter to shape news agendas (Muck Rack, 2019). The backlash against the journal Nature’s endorsement 1 of Joe Biden in the 2020 US presidential election illustrates the risks of political expression in scientific discourse, highlighting its potential to polarise public trust (Zhang 2023). This example raises questions about whether academics should maintain political identities when expressing views, to safeguard public trust in their scholarly independence and expertise.

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the importance of trust to ensure compliance with public health measures that are rooted in hard science (Algan et al., 2021). Concerns also arise over the disconnect between academics and the public on issues like Brexit or populism more broadly, influenced by biases associated with political affiliations (Den Haan et al. 2017, Mede and Schäfer 2020) and differing perspectives on economic policies (Fabo et al. 2020).

The upsides of academic engagement on social media, by providing new and more direct ways of science communication, may inadvertently shape public perceptions of academia through selective topic engagement and differences in communication styles. Unlike traditional media, social media allows for immediate and widespread dissemination of scientific discourse. Most academics are not trained in such communication. Further, not all academics engage with social media, meaning that those who do may disproportionately influence public perceptions of academia through both the specific topics they choose to discuss and the styles and tones in which they communicate. Our new paper explores patterns in academics’ political expressions using a global dataset linking the Twitter profiles of 100,000 scholars to their academic records, spanning institutions across 174 countries and 19 disciplines from 2016 to 2022 (Garg and Fetzer 2024). Leveraging scalable large-language model (LLM) classification techniques, we analyse the content, tone, and substantive focus of their communications.

We document large and systematic variation in politically salient academic expression concerning climate action, cultural, and economic concepts. Views expressed by academics often diverge from the general public opinion in both the topics they focus on and the styles in which they are communicated.

Key findings

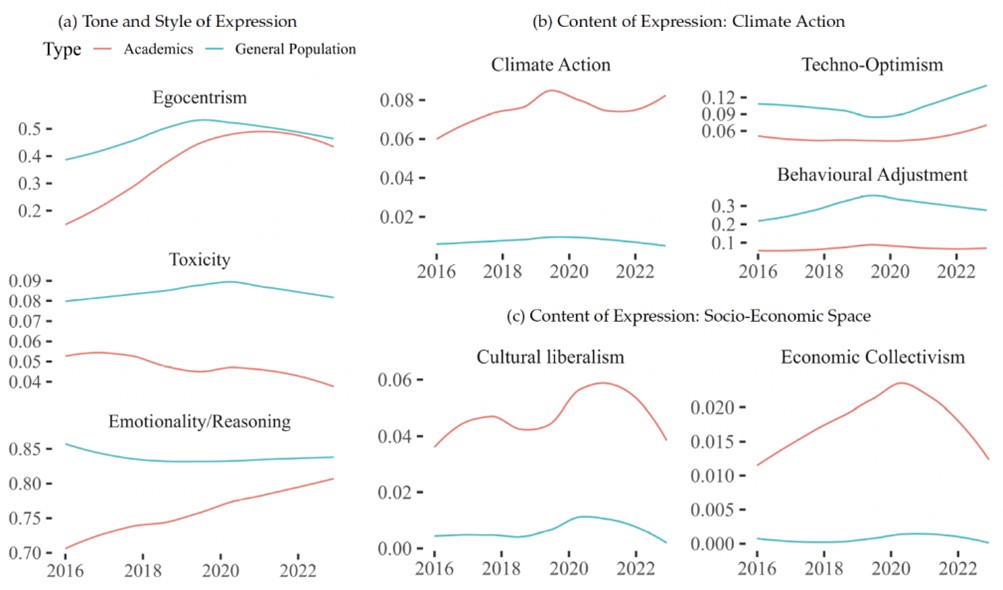

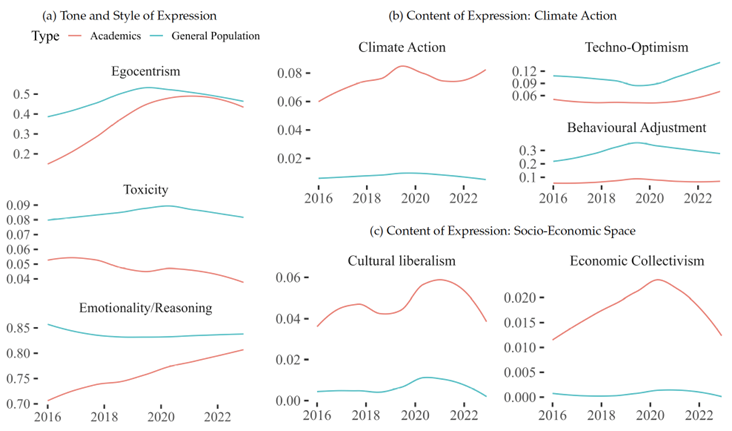

Finding 1: Academics are much more liberal and less toxic on Twitter than the general population

Academics on social media are markedly more vocal on politicised issues compared to the general population. Specifically, academics are 10.7 times more likely to express opinions in favour of climate action, 6.2 times more expressive about virtues of cultural liberalism, and 23.3 times more vocal about advancing economic collectivism than the average US social media user. However, academics consistently exhibit lower levels of toxicity and emotionality in their discourse compared to broader US Twitter users, with toxicity rates halving to around 4%, while the general population maintains rates between 8-9%. This divergence in political expression and communication style may contribute to public misconceptions about academic consensus, potentially affecting public trust in academia and influencing policy debates.

Figure 1 Differences in academic expression between academics and general population in the US

Note: This figure explores the divergences in expression between academics and the general US Twitter population, leveraging two distinct datasets: one comprising tweets from 100,000 US-based academics and another from a sample of 60,000 users representative of the general US Twitter population. The analysis highlights notable differences in both behavioural expression and political stances from January 2016 to December 2022.

Finding 2: American professors tend to be more egocentric and toxic on social media, but professors from other countries tend to be nicer than average

We find big differences in the tone and style of expression between academics, characterised by their field, institutional ranking, gender, and country of affiliation. Academics based in the US and those from top-ranked institutions tend to exhibit higher levels of egocentrism and toxicity on social media. In contrast, academics from other countries generally demonstrate lower levels of toxicity in their online discourse. We also find that humanities scholars and academics with extensive Twitter reach but lower academic prestige display heightened egocentrism. Conversely, academics with lower Twitter reach, regardless of academic standing, and those associated with top 100 universities, exhibit elevated toxicity levels compared to their counterparts.

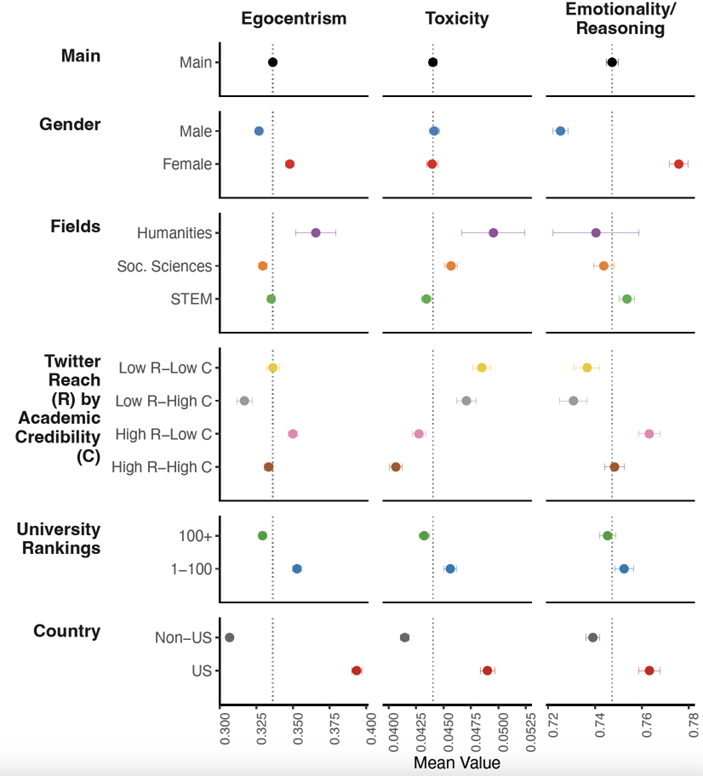

Figure 2 How academics express themselves online: Average by author characteristics

Note: This figure presents the average levels of three behavioural metrics—Egocentrism, Toxicity, and Emotionality/Reasoning—quantified from tweets by a balanced panel of academics from 2016 to 2022, using data linking 100,000 Twitter profiles to their academic profiles. Each panel categorises data by specific groups such as gender, fields, Twitter reach, and academic credibility, university rankings, and country. 95% confidence intervals are indicated by error bars.

Finding 3: Climate action: Discipline polarisation and expert selection

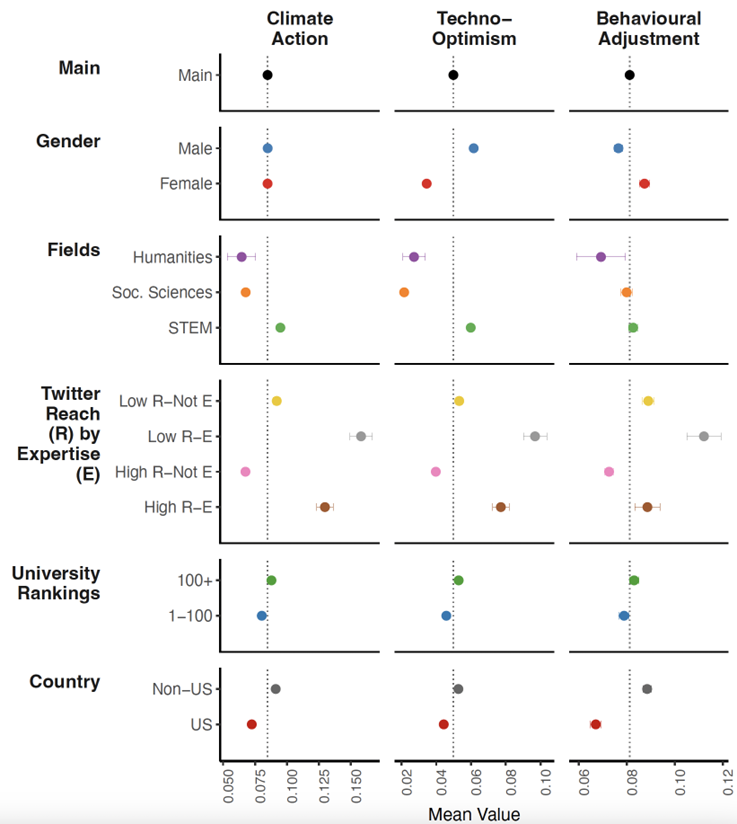

On average, academics are 10.7 times more vocal in advocating for climate action. Male academics exhibit a stronger preference for technological solutions over behavioural adjustments to tackle climate change. STEM scholars prioritise technological solutions, reflecting their focus on innovation and engineering approaches, while social sciences and humanities scholars often emphasise behavioural adjustments and societal transformations as primary solutions. This diversity in academic emphasis allows policymakers to select experts whose perspectives align with their policy goals. Moreover, academics affiliated with top-ranked US universities, and those with larger social media followings but lacking expertise in climate issues, show relatively lower support for proactive climate measures.

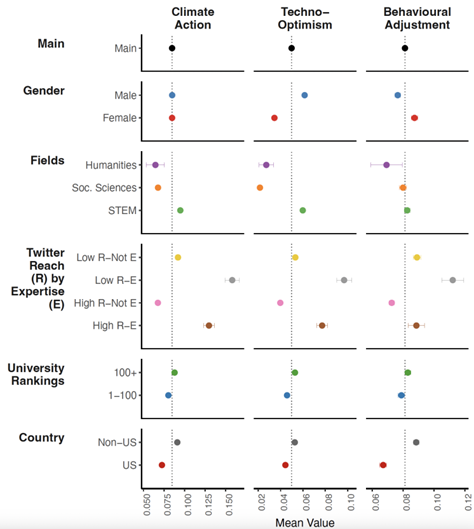

Figure 3 How academics talk about climate action online: Average by author characteristics

Note: This figure illustrates academics’ average stances on three pivotal climate change policy topics—Climate Action, Techno-Optimism, and Behavioural Adjustment—across different academic groups and personal characteristics, using a sample of 138 million tweets made by 100,000 academics between 2016 and 2022. 95% confidence intervals are indicated by error bars.

Implications

The over-representation of certain views – especially from high-reach, low-expertise academics – and the under-representation of other views could result in distorted or poor communication of science. Given these complexities, it is crucial for the academic community to engage in a more inclusive and balanced manner, ensuring that the marketplace of ideas on social media enriches rather than distorts public discourse and policy formulation. Further research should aim to quantify the impact of these ideological divisions on public trust and explore strategies for mitigating potential biases in academic communication on social media. Additional research is required to explore why academics express themselves politically, considering motivations such as name recognition, ideological drive, and the desire to share or evangelise knowledge.

Authors’ note: For a more detailed analysis and access to the dataset, please refer to our full research paper (Garg and Fetzer 2024) and visit our project website for additional results and data release information.

29 maggio 2024

LARGE, BROAD-BASED MACROECONOMIC AND FINANCIAL EFFECTS OF NATURAL DISASTERS

Sandra Eickmeier, Josefine Quast, Yves Schüler

(synthesis; full article 26 may 2024 Vox Eu CEPR https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/large-broad-based-macroeconomic-and-financial-effects-natural-disasters)

Abstract: As the planet warms, the escalation in both frequency and severity of natural disasters be-comes a pressing concern. This column uncovers significant, sustained adverse effects of natural disasters on the US economy and financial markets. Disasters disrupt economic ac-tivity across labour, production, consumption, investment, and housing sectors. These dis-ruptions stem from increased financial risk and uncertainty, declining confidence, and height-ened awareness of climate change. Additionally, disasters cause a temporary spike in con-sumer prices, primarily due to surges in energy and food costs. The findings underscore the critical need for immediate action against climate change and the enhancement of economic and financial resilience to mitigate these impacts.

Keywords: climate change, natural disasters, financial markets, consumer prices, macroeconomic policy, US economy

As climate change intensifies, its impacts become increasingly undeniable. July 2023 stands out as the hottest month ever recorded on Earth (Thompson 2023). Projections indicate that the frequency and severity of extreme weather events, including natural disasters, will continue to escalate with advancing climate change (IPCC 2014, 2022). As the bulk of the social and economic costs are yet to fully materialise, discussions among economists and policymakers regarding the economic and political ramifications of climate change are gaining momentum (e.g. Carney 2015, Batten 2018, Olovsson 2018, Rudebusch 2019, Batten et al. 2020, Lagarde 2020, ECB 2021, Vives et al. 2021, Gagliardi et al. 2022, Pleninger 2022).

Indeed, the repercussions of climate change inevitably intersect with the primary objectives of central banks and fiscal authorities, despite climate change mitigation not being their primary mandate. For instance, central banks must deepen their understanding of how natural disasters and broader climate change phenomena impact economic activity, inflation, and financial stability, along with comprehending the transmission mechanisms underlying these impacts. For fiscal authorities, understanding these impacts is essential as well. Climate change could strain public debt levels, complicating their management and potentially heightening the vulnerability of public finances. Anticipating and accommodating the impact of climate change is thus crucial for the policy decisions of central banks and fiscal authorities and, more broadly, for their support of the societal transition to a carbon-neutral economy.

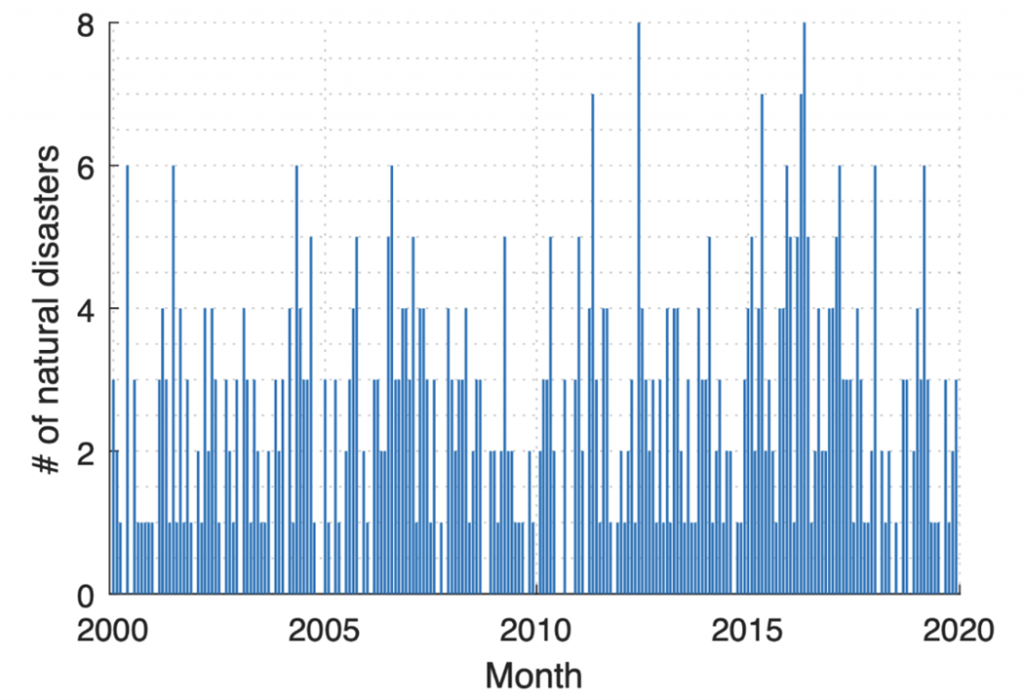

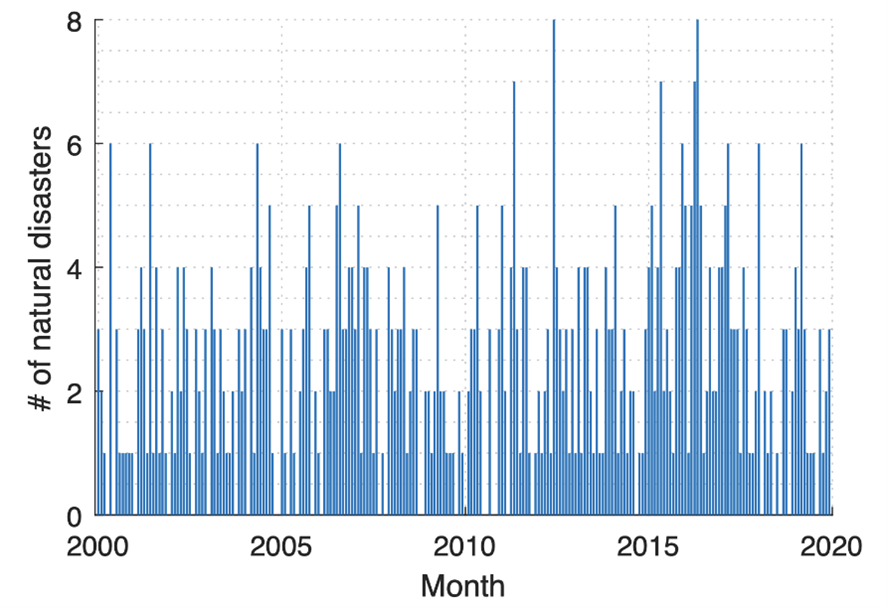

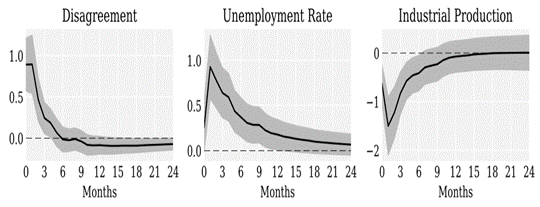

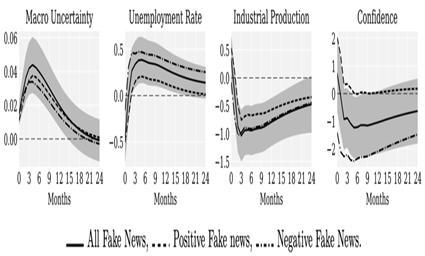

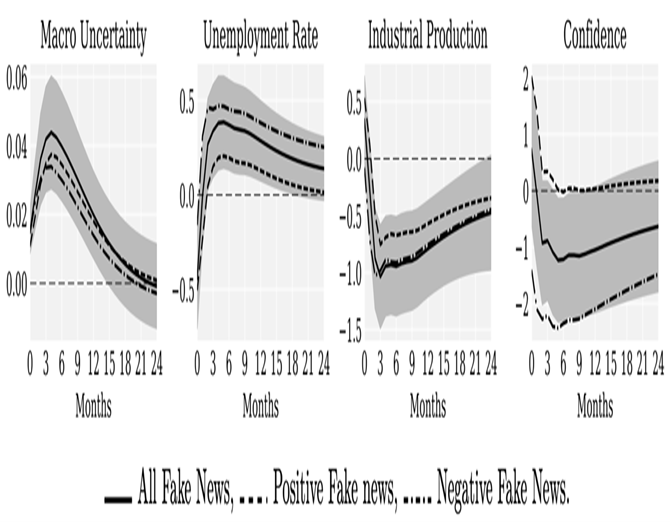

In Eickmeier et al. (2024), we examine the dynamic transmission of natural disasters to the US aggregate economy. We focus on those disasters that are expected to intensify due to climate change, i.e. severe floods, storms, and extreme temperature events. We rely on local projections using monthly data over the pre-pandemic sample since 2000. Our impulse variable reflects the number of natural disaster events in the US in a given month (Figure 1), and we examine the effect of a one standard deviation increase in that variable (which amounts to 1.7 disasters). In this column, we show responses of selected variables to the disasters. The full set of impulse responses can be found in Eickmeier et al. (2024).

Figure 1 Number of natural disasters per month in the US

Notes: Number of extreme temperature events, floods, and storms in a given month.

Profound and widespread adverse effects of natural disasters

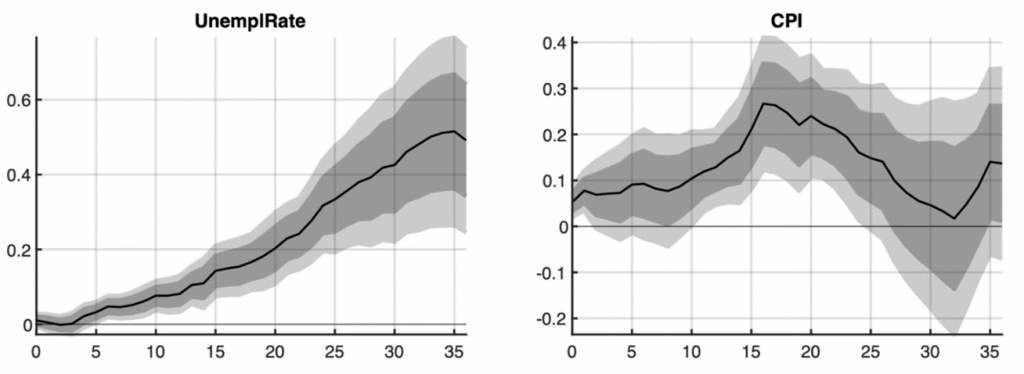

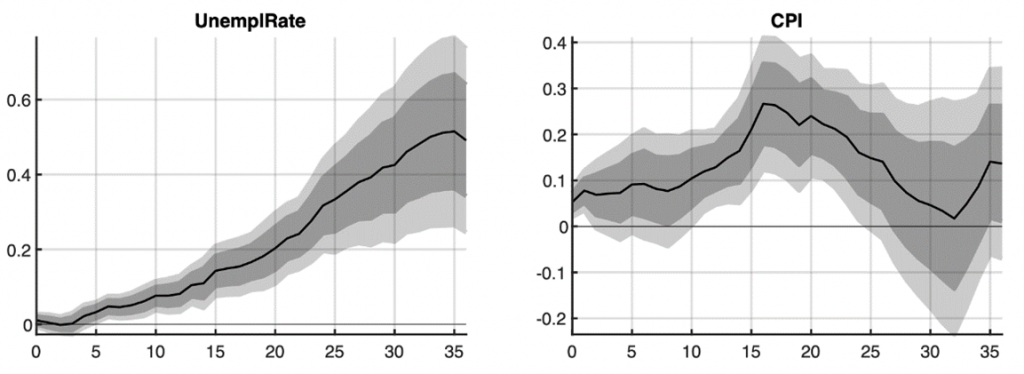

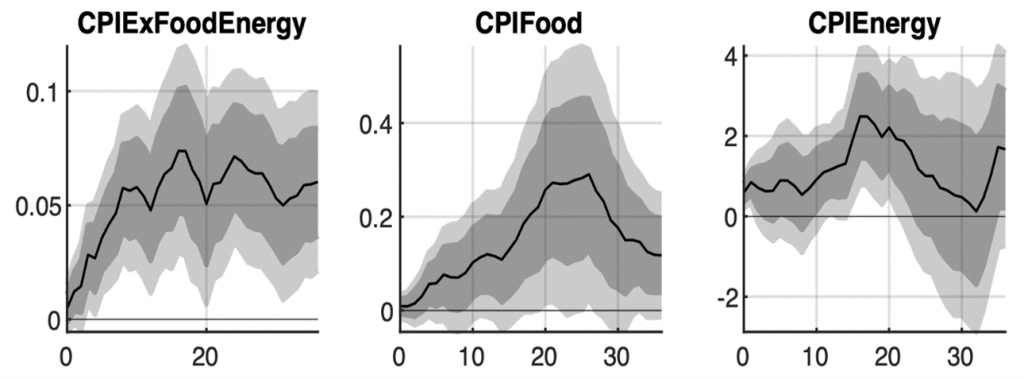

We find that natural disasters trigger significant and enduring negative aggregate impacts on the real economy. The unemployment rate rises gradually and persistently by 0.5 percentage points (Figure 2). The real effects are broad-based, as they manifest across various sectors, including labour and housing markets, production, consumption, and investment. Furthermore, our analysis reveals that disasters temporarily elevate consumer prices, likely driven by transient increases in energy and food costs (see Figure 3).

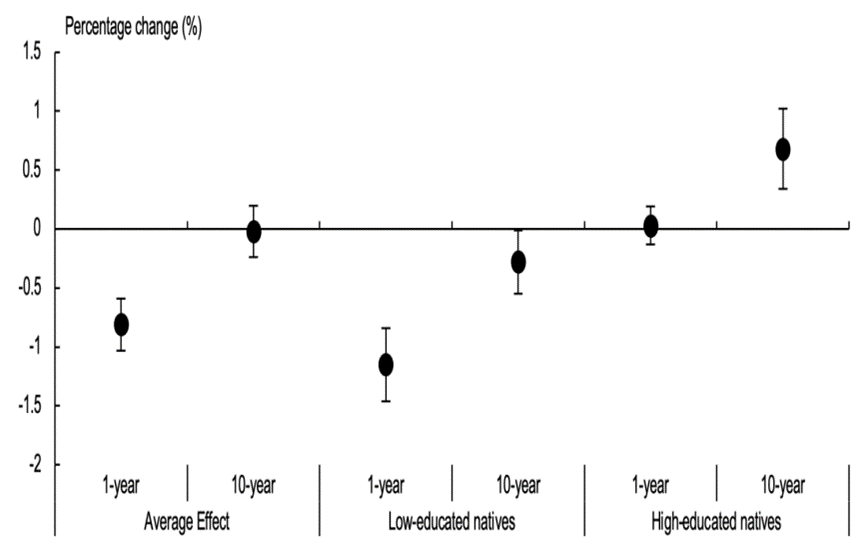

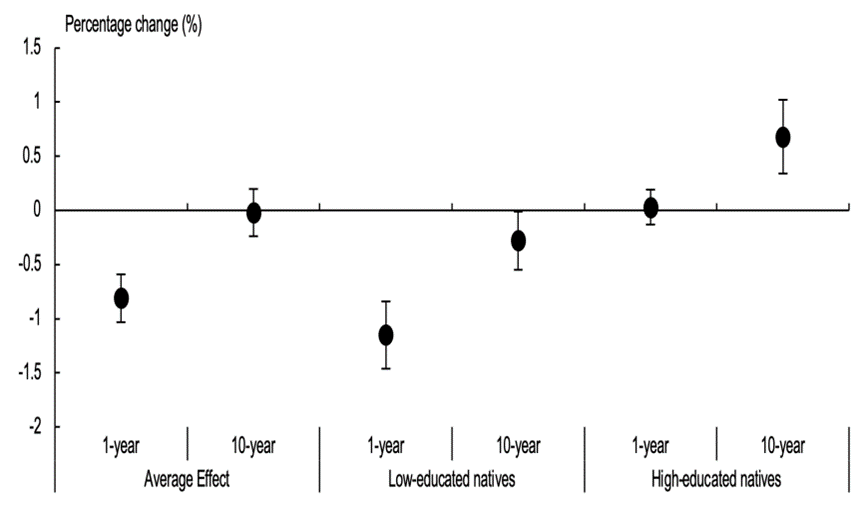

Figure 2 Impulse responses of unemployment rate (percentage points) and consumer prices (%)

Notes: Grey areas indicate 68% and 90% confidence bands. x-axis: months.

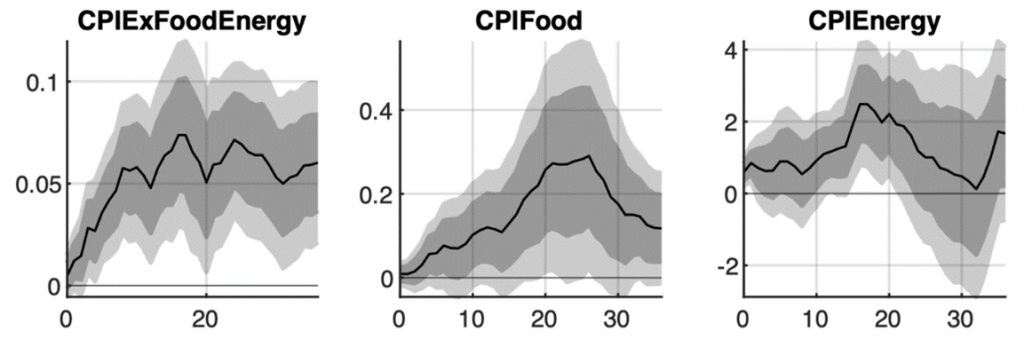

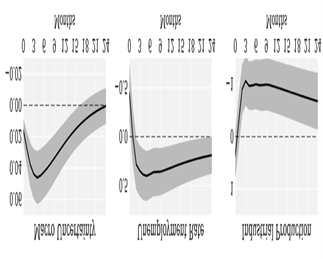

Figure 3 Impulse responses of core consumer prices, food prices, and energy prices (%)

Notes: CPIExFoodENergy: consumer price index excluding food and energy prices, CPIFood: food-specific consumer price index, CPIEnergy: energy-specific consumer price index. Grey areas indicate 68% and 90% confidence bands. x-axis: months.

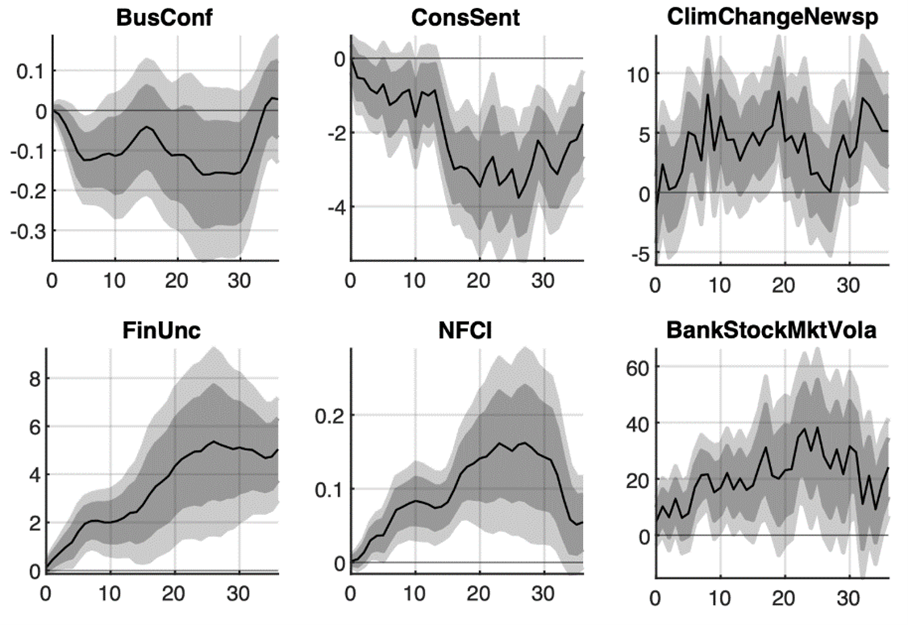

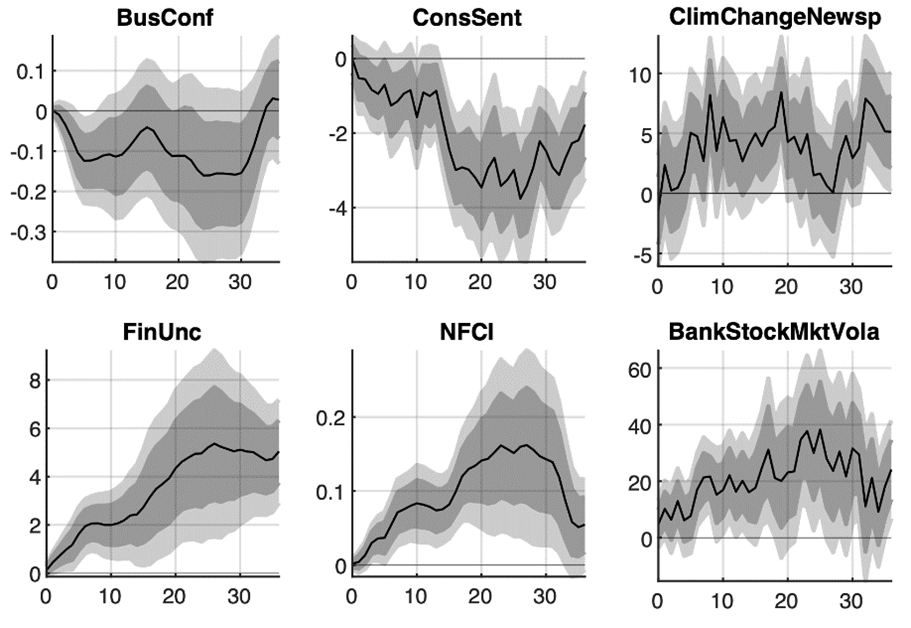

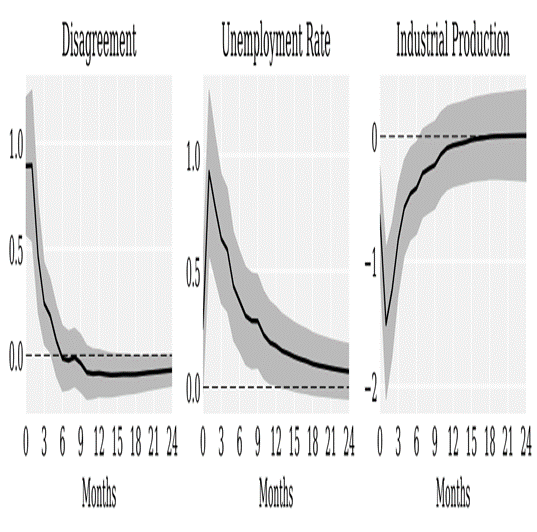

The adverse real effects can be attributed to a widespread decline in confidence, an increase in uncertainty, a tightening of broad financial conditions, encompassing financial risk perceptions, and heightened awareness of climate change (see Figure 4). Indeed, climate attention can serve as an additional channel of transmission. The way individuals perceive the link between natural disasters and climate change likely influences their adaptation strategies, preferences, and broader behaviour, thereby impacting the real economy. We also observe a widespread rise in bank risk and the economy’s susceptibility to future bank risk following the disasters, coupled with a decrease in holdings of (comparatively secure) treasury securities. Conversely, banks appear to be adjusting their portfolios toward safer business and real estate loans, potentially to mitigate the heightened risk.

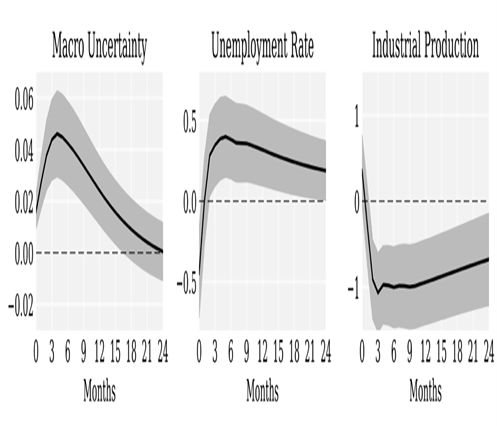

Figure 4 Impulse responses of confidence, media attention toward climate change, and financial uncertainty and risk (%)

Notes: BusConf: business confidence index, ConsSent: consumer sentiment, ClimChangeNewsp: newspaper coverage on climate change. Financial uncertainty based on Jurado et al. (2015), NFCI (in ordinary units): Chicago Fed national financial conditions index, BankStockMktVola: bank stock market volatility. Grey areas indicate 68% and 90% confidence bands. x-axis: months.

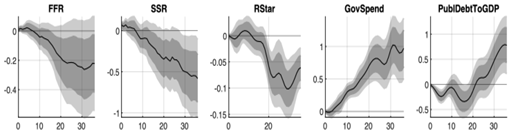

Monetary and fiscal policy variables move in the direction that could contain negative macroeconomic impacts (see Figure 5). Anchored inflation expectations appear to help contain price pressures. However, we find a persistent increase in public debt relative to GDP, exposing the US government to heightened vulnerability in future adverse scenarios. Furthermore, our results suggest a long-lasting decline of r star, limiting future space to manoeuvre for monetary policy as well.

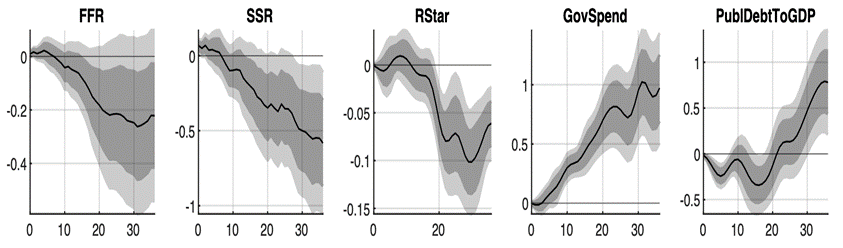

Figure 5 Impulse responses of monetary policy and fiscal variables (% for government spending, percentage points for all other variables)

Notes: FFR: fed-eral funds rate, SSR: shadow short rate provided by Wu & Xia (2016), RStar: one-sided estimate for r-Star by Laubach & Williams (2003), GovSpend: government total expenditures, PublDebtToGDP: total public debt in % of GDP. Grey areas indicate 68% and 90% confidence bands. x-axis: months.

Our results are robust against a large variety of alterations. For instance, we consider individual disaster types, i.e. storms, floods, extreme temperature events, separately; we exclude Hurricane Katrina and the subsequent months from the analysis; we also account for persistence of the impulse variable; and we vary the lag structure of our local projections setup. In a complementary analysis, we analyse the impact of media attention toward climate change on the macroeconomy and find effects on the unemployment rate and consumer prices that are comparable to those following natural disasters. Furthermore, we demonstrate that the effects of natural disasters at the aggregate level differ markedly from their local impacts, reconciling studies which consider local effects of local disasters and those which examine aggregate effects.

As a caveat, just like previous empirical papers, our analysis captures past adjustments. Yet, most of the costs and adjustments are yet to materialise as natural disasters are projected to intensify and occur more frequently. Furthermore, as people increasingly associate these events with climate change, the manner in which the economy adjusts will critically hinge upon individual and collective behavioural responses, making their duration, sign, or size challenging to predict. Despite these uncertainties, we feel confident that our research contributes to a better understanding of the aggregate effects of natural disasters and informs policymakers on possible interventions which could lead to better outcomes.

Summary

Overall, our analysis underscores the profound and widespread negative impacts of natural disasters on the real economy, financial markets, and crucial policy variables. This highlights the urgent need for immediate actions to combat climate change and bolster economic and financial resilience. While our findings indicate that macroeconomic policies have provided some support during these disasters, suggesting possible ways to mitigate their economic impacts, the sustainability of these measures remains in question amidst ongoing climate change. Specifically, as climate change continues to exert downward pressure on r star and elevate public debt levels, the effectiveness of monetary and fiscal policies in managing the economic repercussions of natural disasters may be compromised. Enhancing economic and financial resilience against such shocks becomes increasingly paramount, underscoring the need for immediate and strategic actions to combat climate change and its far-reaching effects.

21 maggio 2024

THE ECONOMICS OF SOCIAL MEDIA

Guy Aridor, Rafael Jiménez-Durán, Ro’ee Levy, Lena Song

(synthesis; full article 20 may 2024 Vox Eu CEPR https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/economics-social-media )

Abstract: The growing interest in regulating the market power and influence of social media platforms has been accompanied by an explosion in academic research. This column synthesises the research on social media and finds that while it has made dramatic progress in the last decade, it mostly focuses on Facebook and Twitter. More research is needed on other platforms that are growing in usage, such as TikTok, especially since these platforms tend to produce different content, distribute content differently, and have different consumers. Studying these changes is crucial for policymakers to design optimal regulation for social media’s future.

Keywords: digital markets, social media, algorithms, social behavior. Digital Markets Act Digital Services Act

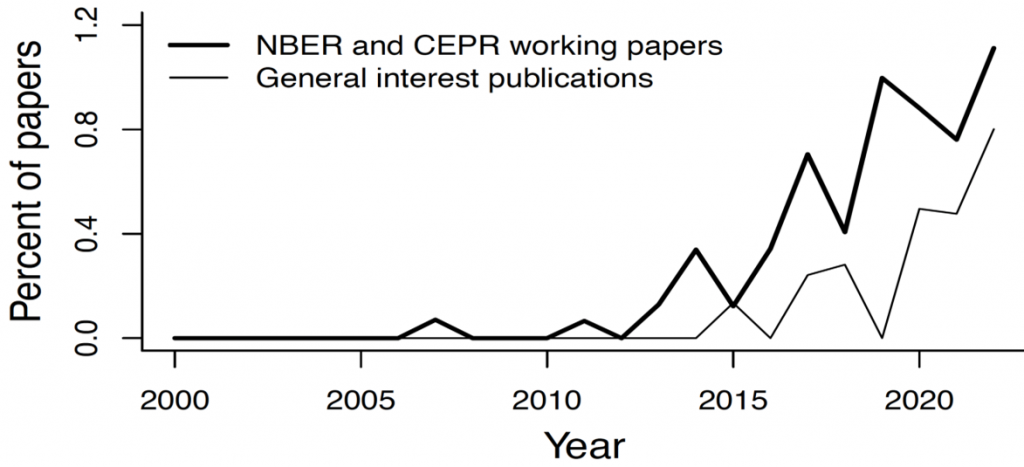

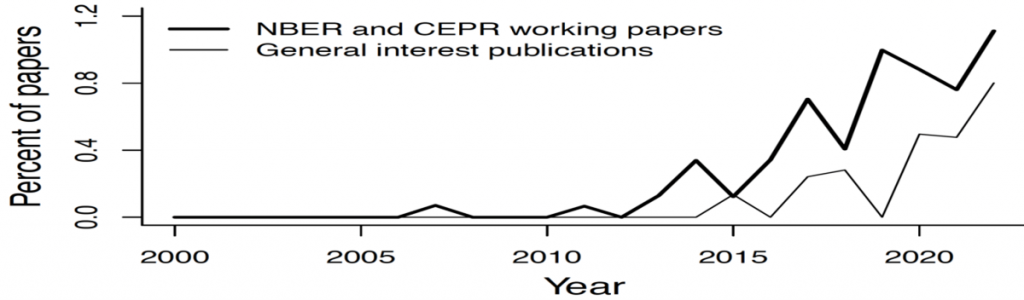

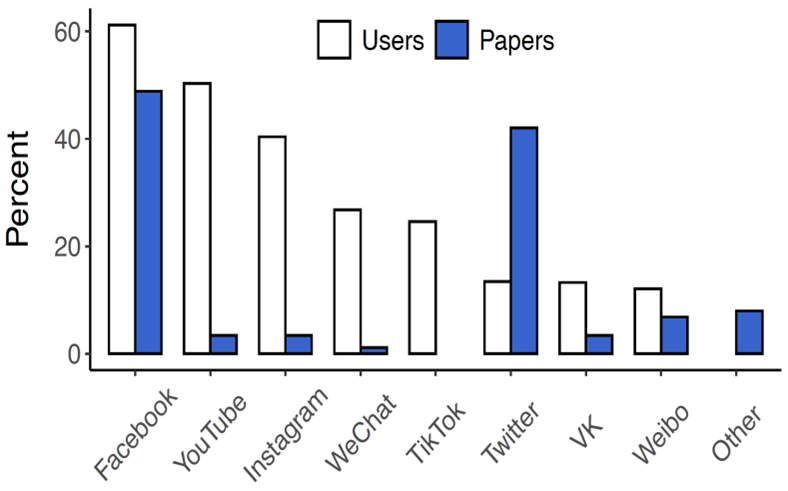

The Digital Markets Act (Scott Morton and Caffarra 2021) and the Digital Services Act highlight the growing interest in regulating the market power and influence of social media platforms. This heightened policy interest, paired with the explosion in academic research studying social media (pictured in Figure 1), generates a demand for a synthesis of the rapidly expanding literature in order to help guide the many policy debates. In a recent paper (Aridor et al. 2024a), we synthesise and organise the literature around the three stages of the life cycle of social media content: (1) production, (2) distribution, and (3) consumption.

Figure 1 Social media research in economics

Source: Aridor et al. (2024)

Production of content

Social media platforms rely on user-generated content to attract users. Unlike traditional media that can directly shape content through editorial processes, social media platforms must rely on platform design – features, incentives, and rules – to influence content production. The challenge for platforms is to incentivise the creation of content that attracts user engagement and advertisers, while deterring the creation of harmful content such as misinformation and hate speech.

There is evidence that the production of content responds to different types of incentives. Non-monetary incentives such as peer awards or feedback (including badges, reactions, likes, and comments) have been shown to moderately increase the amount of content produced in the short run (Eckles et al. 2016). While monetary incentives could theoretically crowd out prosocial motives, the literature has also found strong positive effects of monetary incentives, such as ad-revenue sharing programmes, on content creation (Abou El-Komboz et al. 2023). As opposed to quantity, the quality of content produced – proxied, for instance, by the subsequent number of likes received – seems relatively more difficult to influence. Non-monetary incentives tend to have small effect sizes on quality (Zeng et al. 2022, Srinivasan 2023) and the evidence for monetary incentives is mixed (Sun and Zhu 2013, Kerkhof 2020).

Due to its social consequences, a policy-relevant dimension of content quality is whether it contains misinformation or ‘toxic content’ (e.g. hate speech). In terms of misinformation, a vast literature studies several types of interventions that seek to deter the production – mostly the re-sharing – of false articles, while keeping constant or even increasing the sharing of truthful information (Kozyreva et al. 2022, Pennycook and Rand 2022, Martel and Rand 2023). When comparing across interventions, nudging or prompting users to think about the prevalence of misinformation (Guriev et al. 2023) and digital literacy campaigns that train users to identify emotional manipulation (Athey et al. 2023) seem to be particularly effective. In terms of toxic content, reducing users’ exposure to toxicity (Beknazar et al. 2022) and some types of counterspeech – messages that reproach the producers of toxic content (Munger 2017) – have been found to deter the production of this type of content with small effect sizes. ‘Harder’ sanctions such as post deletions (Jiménez Durán 2022) tend to have null or at best small effect sizes.

Distribution of content

After content is produced, platforms distribute it to users. The distribution of content could be affected by users’ social networks and the platforms’ algorithms. There is an ongoing debate on whether and how to regulate the content that algorithms promote and downrank. Specifically, there is a concern that by promoting like-minded or low-quality content, algorithms may distort beliefs or polarize users (Aral 2021, Campante et al. 2023). The best evidence on this topic comes from Facebook. Based on both experimental variation (Levy 2021) and internal data (Gonzlez-Bailon et al. 2023), there is growing evidence that Facebook’s algorithms tend to promote like-minded content, though the effects are still being debated (Messing 2023). In terms of content quality, Facebook’s algorithm may increase the amount of uncivil content but also decrease exposure to untrustworthy accounts (Gonzalez-Bailon et al. 2023, Guess et al. 2023). These results are consistent with social media platforms trying to maximise engagement, while perhaps downranking specific posts due to other incentives, such as the platforms’ reputation. Other concerns regarding the algorithm have received less support in the literature. For example, YouTube’s recommendation system does not seem to drive users into extreme rabbit holes (Hosseinmardi et al. 2021, Chen et al. 2023).

In addition to distributing organic content, platforms distribute ads to users. In contrast to traditional advertising, ads on social media can accurately target users based on various characteristics and thus are especially valuable (Gordon et. al 2023; Tadelis et. al 2023). A key policy debate with regard to social media advertisements is how to balance the trade-off between the consumer welfare gains from privacy and the dependence of firms on advertising revenues. On the one hand, personal data are clearly valuable for firms. Wernerfelt et al. (2022) find that removing access to off-platform data would increase median acquisition costs for Facebook advertisers by 37%, and Aridor et al. (2024b) find that Apple’s App Tracking Transparency policy – which allowed consumers to opt out of sending this data to applications – led to significant revenue losses for Facebook-dependent direct-to-consumer firms. On the other hand, consumers may highly value maintaining the privacy of their data. Lin et. al (2023) elicit incentive-compatible valuations for consumers’ data and find that the distribution of privacy preferences is heavily skewed and that consumers most value protecting the privacy of their friend network and posts on the platform.

Consumption of content

Consumers allocate their time between consuming content served by the platform and off-platform activities. Their choices are influenced by consumption spillovers where others’ consumption choices influence how people use social media, habit formation where consumption today makes people want to use more in the future, and self-control problems where people use social media more than they would like to (Eckles et al. 2016, Allcott et al. 2020, Allcott et al. 2022, Aridor 2023).

These choices affect the wellbeing of consumers. Experiments eliciting how much users need to be paid to stop using social media find that users highly value its access (Brynjolfsson, Collis, and Eggers 2019; Brynjolfsson et al. 2023). However, Bursztyn et al. (2023) point out that nonusers could derive negative utility from others’ social media usage and find evidence for negative consumer welfare once this spillover to non-users is accounted for. This explanation is consistent with empirical evidence suggesting that social media has adverse effects on subjective wellbeing and mental health (Allcott et al. 2020, Mosquera et al. 2020, Braghieri et al. 2022). Importantly, these results do not imply that consumer welfare is negative at every level of social media consumption; some level of social media use may be beneficial.

Social media consumption can also have both positive and negative aggregate impacts. On the positive side, social media has been shown to increase news knowledge and facilitate protest in democracies (Fergusson and Molina 2021, Guess et al. 2023a). On the flip side, social media has been linked to beliefs influenced by misinformation and offline hate crimes (Allcott and Gentzkow 2017, Müller and Schwarz 2021, Jiménez Durán et al. 2022). The evidence on polarisation and voting is more mixed and context-dependent (Levy 2021, Garbiras-Díaz and Montenegro 2022, Guess et al 2023a, 2023b, Nyhan et al. 2023, Fujiwara et al. forthcoming). These effects operate through several channels, including social media as a platform for exposure to persuasive content, facilitation of coordinated actions, and influence on people’s perceptions of others.

Beyond looking at on-platform and off-platform behavior, recent research has studied consumers’ substitution patterns across platforms. Amid concerns that the market for social media applications has become too concentrated, measuring substitution patterns is crucial for assessing the degree of market concentration. There is evidence that consumers substitute not only to other social media apps, but also to communication apps and non-digital activities (Collis and Eggers 2022, Aridor 2023).

Concluding remarks

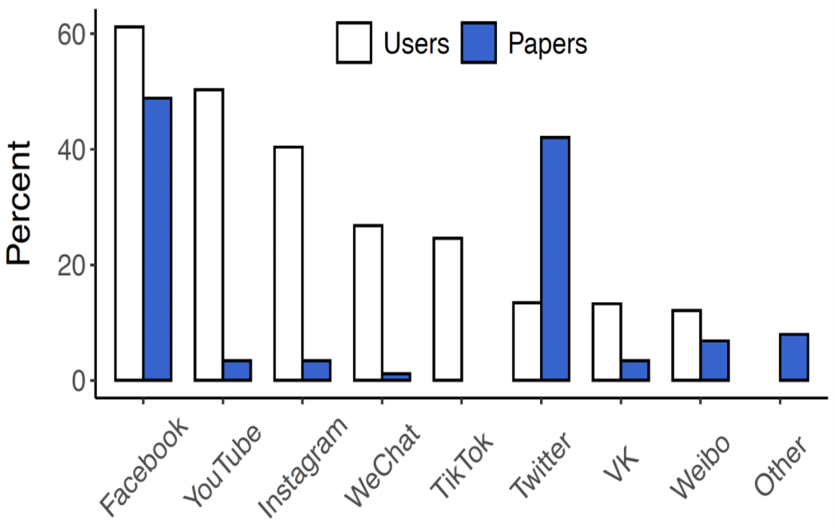

In this column, we show that research on social media has made dramatic progress in the last decade. However, social media is rapidly changing, both in terms of the platforms used and the content produced, distributed, and consumed. Figure 2 shows that Facebook remains the most dominant platform, but that it faces competition from newer platforms. The figure also shows that academic research mostly focuses on Facebook and Twitter. More research is needed about other platforms that are growing in usage, such as TikTok, especially since these platforms tend to produce different content (e.g. more videos), distribute content differently (rely on their algorithm and not on one’s social network) and have different consumers (e.g. more content consumed by teenagers). Studying these changes is crucial for policymakers to design optimal regulation for social media’s future.

Figure 2 Platform representation in the economics literature

Source: Aridor et al., (2024)

15 maggio 2024

HOW GEOPOLITICS IS CHANGING TRADE

Costanza Bosone, Ernest Dautović Michael Fidora, Giovanni Stamato

(synthesis; full article 14 may 2024 https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/how-geopolitics-changing-trade)

Abstract: There has been a rise in trade restrictions since the US-China tariff war and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. This column explores the impact of geopolitical tensions on trade flows over the last decade. Geopolitical factors have affected global trade only after 2018, mostly driven by deteriorating geopolitical relations between the US and China. Trade between geopolitically aligned countries, or friend-shoring, has increased since 2018, while trade between rivals has decreased. There is little evidence of near-shoring. Global trade is no longer guided by profit-oriented strategies alone – geopolitical alignment is now a force.

Keywords: international trade, geopolitics, friend-shoring, global trade

Since the global financial crisis, trade has been growing more slowly than GDP, ushering in an era of ‘slowbalisation’ (Antràs 2021). As suggested by Baldwin (2022) and Goldberg and Reed (2023), among others, such a slowdown could be read as a natural development in global trade following its earlier fast growth. Yet, a surge in trade restriction measures has been evident since the tariff war between the US and China (see Fajgelbaum and Khandelwal 2022) and geopolitical concerns have been heightened in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, with growing debate about the need for protectionism, near-shoring, or friend-shoring.

The impact of geopolitical distance on international trade

Rising trade tensions amid heightened uncertainty have sparked a growing literature on the implications of fragmentation of trade across geopolitical lines (Aiyar et al. 2023, Attinasi et al. 2023, Campos et al. 2023, Goes and Bekker 2022).

In Bosone et al. (2024), we present new evidence and quantify the timing and impact of geopolitical tensions in shaping trade flows over the last decade. To do so, we use the latest developments in trade gravity models. We find that geopolitics starts to significantly affect global trade only after 2018, which, timewise, is in line with the tariff war between the US and China, followed by the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Furthermore, the analysis sheds light on the heterogeneity of the effect of geopolitical distance by groups of countries: we find compelling evidence of friend-shoring, while our estimates do not reveal the presence of near-shoring. Finally, we show that geopolitical considerations are shaping European Union trade, with a particular focus on strategic goods.

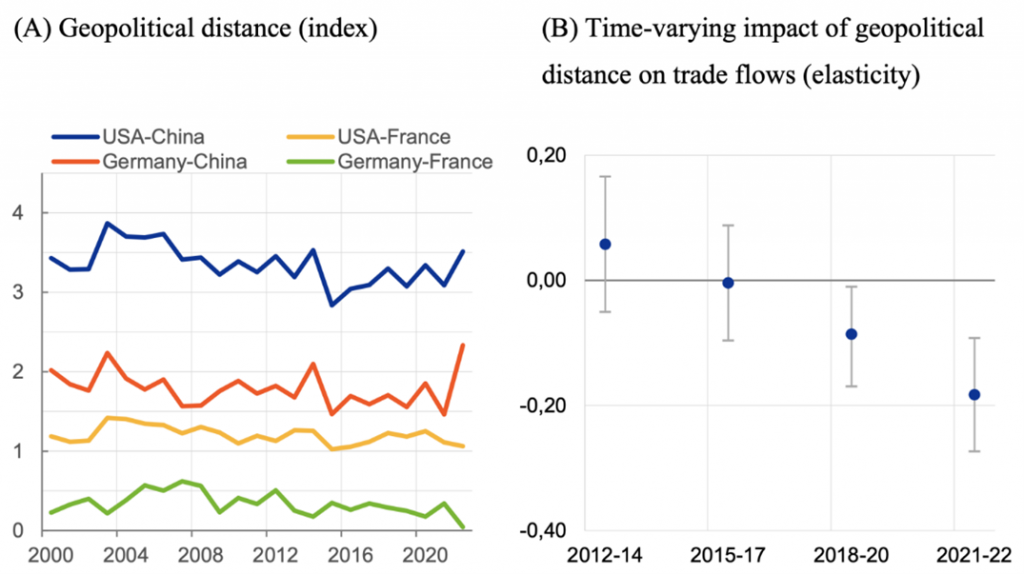

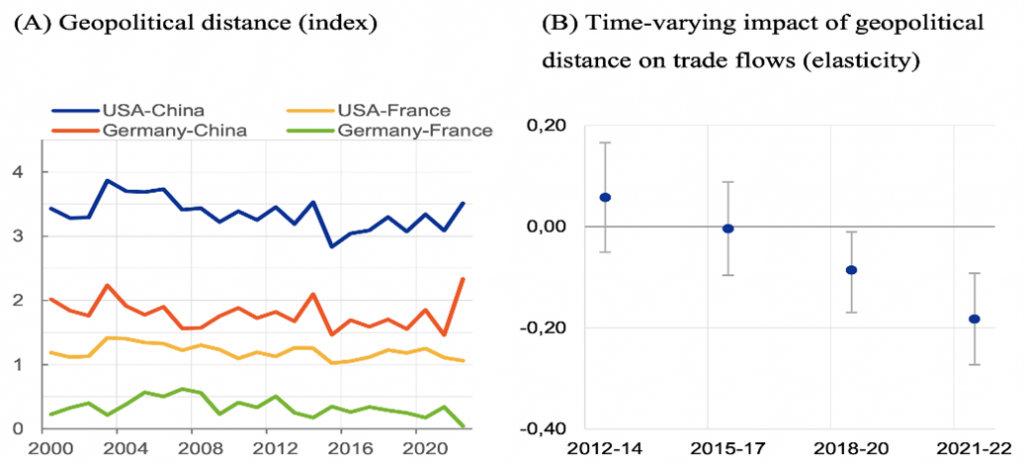

In this study, geopolitics is proxied by the geopolitical distance between country pairs (Bailey et al. 2017). As an illustration, Figure 1 (Panel A) plots the evolution over time of the geopolitical distance between four country pairs: US-China, US-France, Germany-China, and Germany-France. This chart shows a consistently higher distance from China for both the US and Germany, as well as a further increase in that distance over recent years.

Geopolitical distance is then included in a standard gravity model with a full set of fixed effects, which allow us to control for unobservable factors affecting trade. We also control for international border effects and bilateral time-varying trade cost variables, such as tariffs and a trade agreement indicator. This approach minimises the possibility that the index of geopolitical distance captures the role of other factors that could drive trade flows. We then estimate a set of time-varying elasticities of trade flows with respect to geopolitical distance to track the evolution of the role of geopolitics from 2012 to 2022. To the best of our knowledge, we cover the latest horizon on similar studies on geopolitical tensions and trade. To rule out the potential bias deriving from the use of energy flows as political leverage by opposing countries, we use manufacturing goods excluding energy as the dependent variable. We present our results based on three-year averages of data.

Figure 1 Evolution of geopolitical distance between selected country pairs and its estimated impact on bilateral trade flows

Notes: Panel A: geopolitical distance is based on the ideal point distance proposed by Bailey et al. (2017), which measures countries’ disagreements in their voting behaviour in the UN General Assembly. Higher values mean higher geopolitical distance. Panel B: Dots are the coefficient of geopolitical distance, represented by the logarithm of the ideal point distance interacted with a time dummy, using 3-year averages of data and based on a gravity model estimated for 67 countries from 2012 to 2022. Whiskers represent 95% confidence bands. The dependent variable is nominal trade in manufacturing goods, excluding energy. Estimation performed using the PPML estimator. The estimation accounts for bilateral time-varying controls, exporter/importer-year fixed effects, and pair fixed effects.

Sources: TDM, IMF, Bailey et al. (2017), Egger and Larch (2008), WITS, Eurostat, and ECB calculations.

Our estimates reveal that geopolitical distance became a significant driver of trade flows only since 2018, and its impact has steadily increased over time (Figure 1, Panel B). The fall in the elasticity of geopolitical distance is mostly driven by deteriorating geopolitical relations, most notably between the US and China and more generally between the West and the East. These reflect the effect of increased trade restrictions in key strategic sectors associated to the COVID-19 pandemic crisis, economic sanctions imposed to Russia, and the rise of import substituting industrial policies.

The impact of geopolitical distance is also economically significant: a 10% increase in geopolitical distance (like the observed increase in the USA-China distance since 2018, in Figure 1) is found to decrease bilateral trade flows by about 2%. In Bosone and Stamato (forthcoming), we show that these results are robust to several specifications and to an instrumental variable approach.

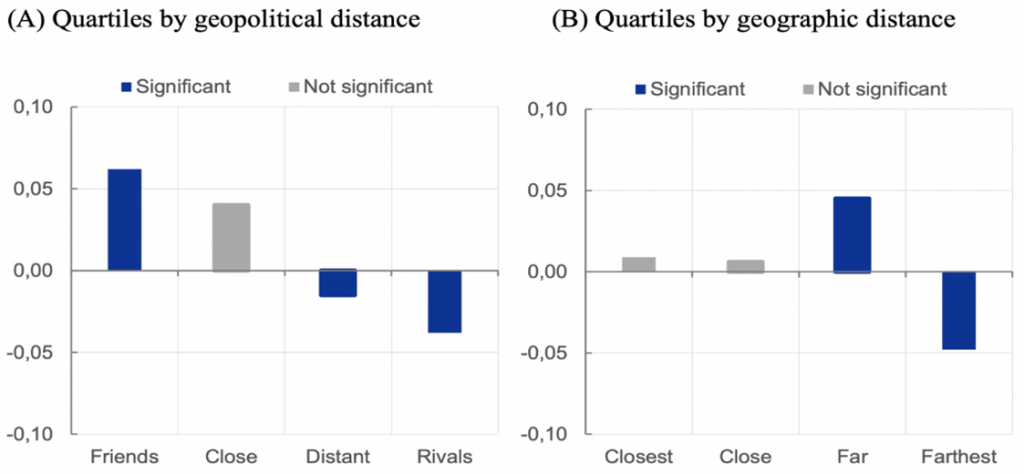

Friend-shoring or near-shoring?

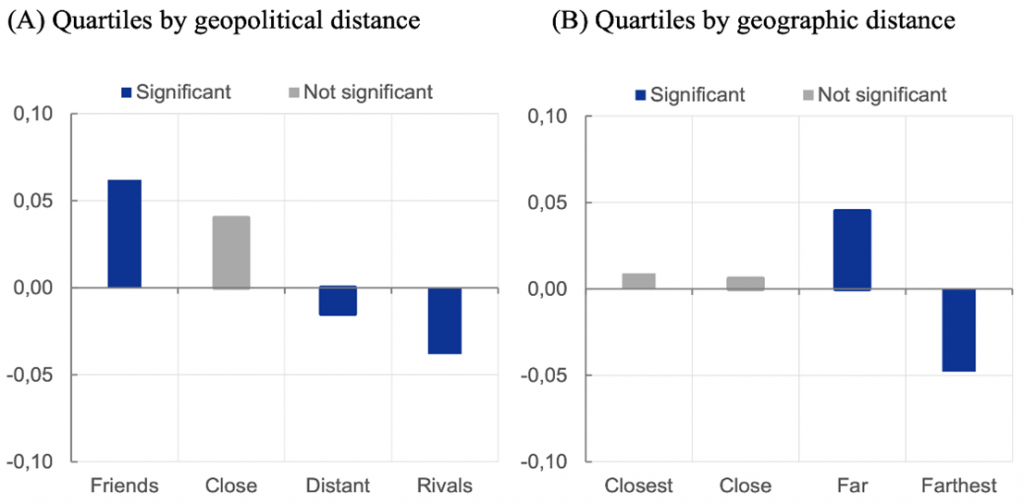

Recent narratives surrounding trade and economic interdependence increasingly argue for localisation of supply chains through near-shoring and strengthening production networks with like-minded countries through friend-shoring (Yellen 2022). To offer quantitative evidence on these trends, we first regress bilateral trade flows on a set of four dummy variables that identify the four quartiles of the distribution of geopolitical distance across country pairs. To capture the effect of growing geopolitical tensions on trade, each dummy is equal to 1 for trade within the same quartile from 2018 and zero otherwise.

We find compelling evidence of friend-shoring. Trade between geopolitically aligned countries increased by 6% since 2018 compared to the 2012–2017 period. Meanwhile, trade between rivals decreased by 4% (Figure 2, Panel A). In contrast, our estimates do not reveal the presence of near-shoring trends (Figure 2, Panel B). Instead, we find a significant increase in trade between far-country pairs, offset by a relatively similar decline in trade between the farthest-country pairs. Overall, shifts toward geographically close partners are less pronounced than toward geopolitically aligned partners.

Figure 2 Impact of trading within groups since 2018 (semi-elasticities)

Notes: Estimates in both panels are obtained by PPML on the sample period 2012–2022 using consecutive years. Please refer to Figure 1 for details on estimation. The effects on each group are identified based on a dummy for quartiles of the distribution of geopolitical distance (panel A) and on a dummy for quartiles of the distribution of geographic distance (panel B) across country pairs. The dummy becomes 1 in case of trade between country pairs belonging to the same quartile since 2018. A semi-elasticity b corresponds to a percentage change of 100*(exp(b)-1).

Sources: TDM, IMF, Bailey et al. (2017), Egger and Larch (2008), WITS, Eurostat, CEPII, and ECB calculations.

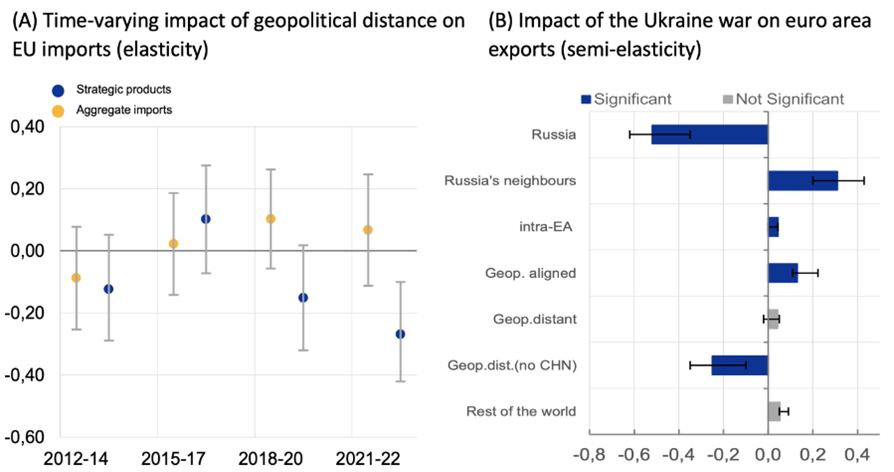

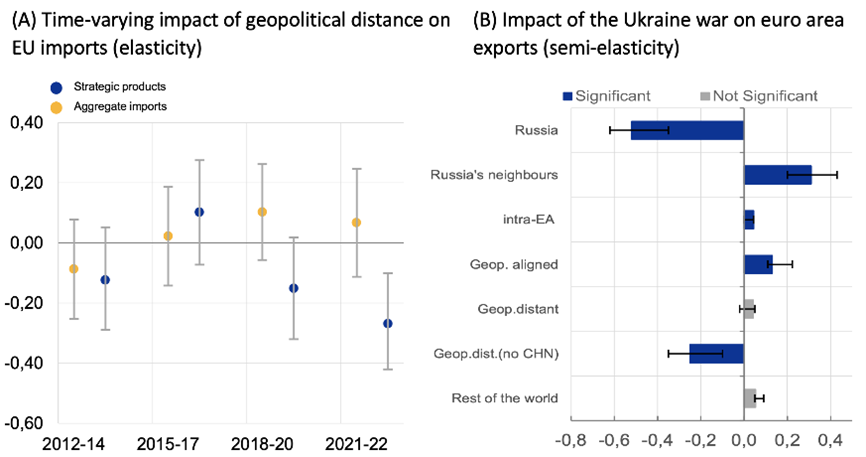

Evidence of de-risking in EU trade

The trade impact of geopolitical distance on the EU is isolated by interacting geopolitical distance with a dummy for EU imports. We find that EU aggregate imports are not significantly affected by geopolitical considerations (Figure 3, Panel A). This result is robust to alternative specifications and may reflect the EU’s high degree of global supply chain integration, the fact that production structures are highly inflexible to changes in prices, at least in the short term, and that such rigidities increase when countries are deeply integrated into global supply chains (Bayoumi et al. 2019). Nonetheless, we find evidence of de-risking in strategic sectors. 1 When we use trade in strategic products as the dependent variable, we find that geopolitical distance significantly reduces EU imports (Figure 3, Panel A).

Figure 3 Impact of geopolitical distance on EU imports and of the Ukraine war on euro area exports

Notes: Estimates in both panels are obtained by PPML on the sample period 2012–2022. Panel A: Dots represent the coefficient of geopolitical distance interacted with a time dummy and with a dummy for EU imports, using 3-year averages of data. Lines represent 95% confidence bands. Panel B: The sample includes quarterly data over 2012–2022 for 67 exporters and 118 importers. Effects on the level of euro area exports are identified by a dummy variable for dates after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Trading partners are Russia; Russia’s neighbours Armenia, Kazakhstan, the Kyrgyz Republic, and Georgia; geopolitical friends, distant, and neutral countries are respectively those countries that voted against or in favour of Russia or abstained on both fundamental UN resolutions on 7 April and 11 October 2022. The whiskers represent minimum and maximum coefficients estimated across several robustness checks.

Sources: TDM, IMF, Bailey et al. (2017), Egger and Larch (2008), WITS, Eurostat, European Commission, and ECB calculations.

We conduct an event analysis to explore the implications of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on euro area exports. We find that the war has reduced euro area exports to Russia by more than half (Figure 3, Panel B), but trade flows to Russia’s neighbours have picked up, possibly due to a reordering of the supply chain. Euro area exports with geopolitically aligned countries are estimated to have been about 13% higher following the war, compared with the counterfactual scenario of no war. We find no signs of euro area trade reorientation away from China, possibly reflecting China’s market power in key industries. However, when China is excluded from the geopolitically distant countries, the impact of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on euro area exports becomes strongly significant and negative.

Concluding remarks

Our findings point to a redistribution of global trade flows driven by geopolitical forces, reflected in the increasing importance of geopolitical distance as a barrier to trade. In this column we review recent findings on geopolitics in trade and their impact since 2018, the emergence of friend-shoring rather than near-shoring, and the interactions of strategic sectors with geopolitics in Europe. In sum, we bring evidence of new forces that now drive global trade – forces that are no longer guided by profit-oriented strategies alone but also by geopolitical alignment.

6 maggio 2024

SHOULD AI STAY OR SHOULD AI GO: THE PROMISES AND PERILS OF AI FOR PRODUCTIVITY AND GROWTH

Francesco Filippucci, Peter Gal, Cecilia Jona-Lasinio, Alvaro Leandro, Giuseppe Nicoletti

(synthesis; full article 2 may 2024 Vox Eu CEPR https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/should-ai-stay-or-should-ai-go-promises-and-perils-ai-productivity-and-growth)

Abstract: There is considerable disagreement about the growth potential of artificial intelligence. Though emerging micro-level evidence shows substantial improvements in firm productivity and worker performance, the macroeconomic effects are uncertain. This column argues that the promise of AI-related economic growth and social welfare hinges on the rate of adoption and its interplay with labour markets. Policies should focus on both domestic and global governance issues – including threats to market competition and increased inequality – and do so rapidly to keep pace with fast-evolving AI.

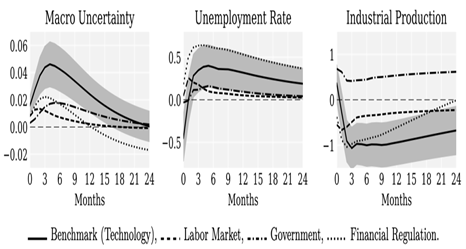

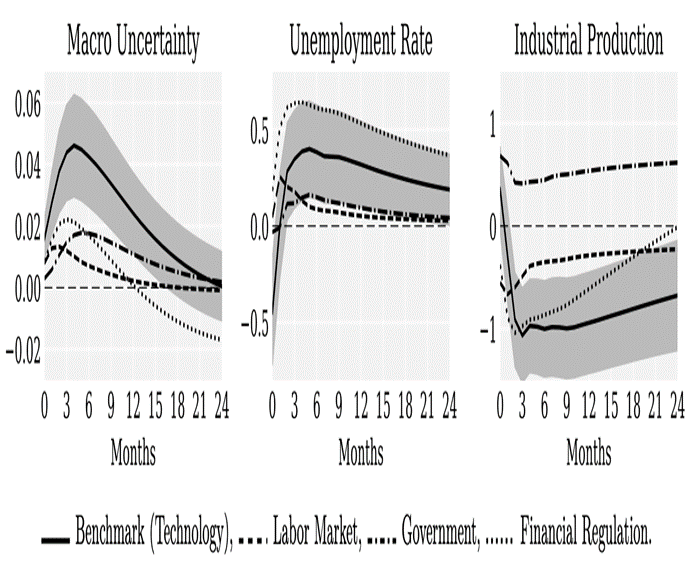

Keywords: productivity and innovation, artificial intelligence, ai growth.

Income and wellbeing gains in advanced economies have been held back by weak productivity performance. The growth rate of labour productivity declined in OECD economies from about 2% annual growth rate between the 1970s and 1990s, to 1% in the 2000s (Goldin et al. 2024, Andre and Gal 2024). This poses a dramatic challenge for ageing societies and makes it harder to allocate resources for the green transition.

There is widespread enthusiasm about the growth potential of rapidly developing artificial intelligence (AI). Some analysts argue that, under reasonable conditions, AI could lead to large and persistent gains, on the order of adding 1–1.5 percentage points to annual growth rates over the next 10–20 years (Baily et al. 2023, Artificial Intelligence Commission of France 2024, McKinsey 2023, Briggs and Kodnani 2023). On the other hand, Acemoglu (2024) contends that the available evidence combined with the economic theory of aggregation supports only moderate total factor productivity and GDP growth impacts, on the order of about 0.1% per year.

Recent work from the OECD provides a broad overview of AI’s impact on productivity and discusses the conditions under which it is expected to deliver strong benefits, with a focus on the role of policies (Filippucci et al. 2024).

AI as a new general-purpose technology

Given its transformative potential in a wide range of economic activities, AI can be seen as the latest general-purpose technology (Agrawal et al. 2019, Varian 2019) – similar to previous digital technologies such as computers and the internet or, going back further, to the steam engine and electricity. From an economic perspective, AI can be seen as a production technology combining intangible inputs (skills, software, and data) with tangible ones (computing power and other hardware), to produce three broad types of outputs:

- Content, such as texts or images (generative AI)

- Predictions, optimisations, and other advanced analytics, which can be used to assist with or fully automate human decisions (non-generative AI)

- Physical tasks when combined with robotics (including autonomous vehicles).

Additionally, AI has some peculiar features, even compared to previous digital technologies. These include the potential for being autonomous (less dependent on human inputs) and the capacity for self-improvement, by learning from patterns in unstructured data or leveraging feedback data about its own performance. Altogether, these features imply that AI can boost not only the production of goods and services but also the generation of ideas, speeding up research and innovation (Aghion et al. 2018).

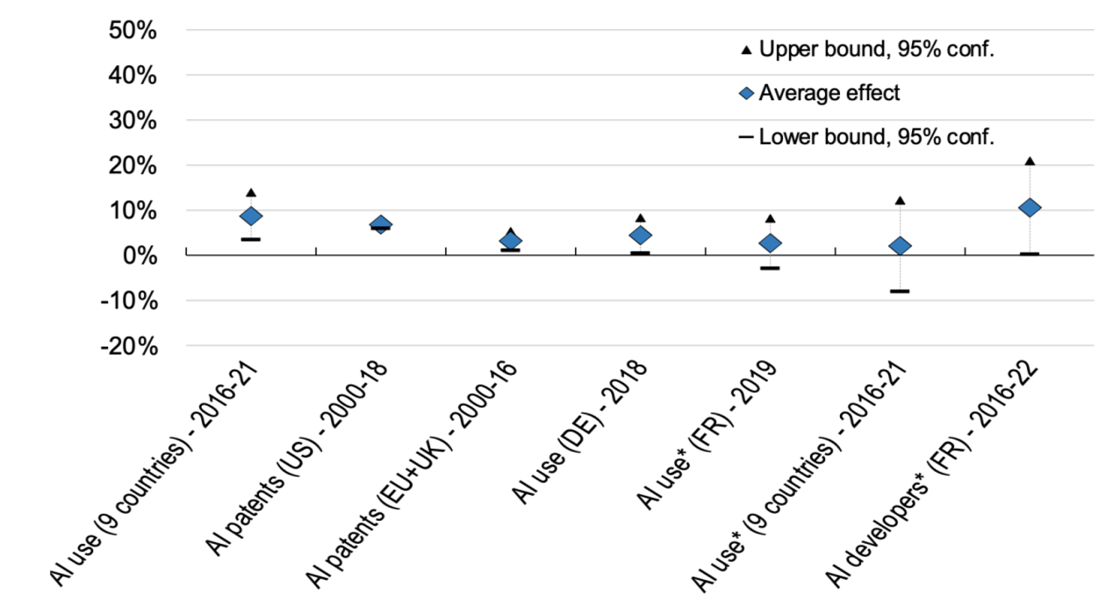

Initial micro-level evidence shows large productivity and performance gains

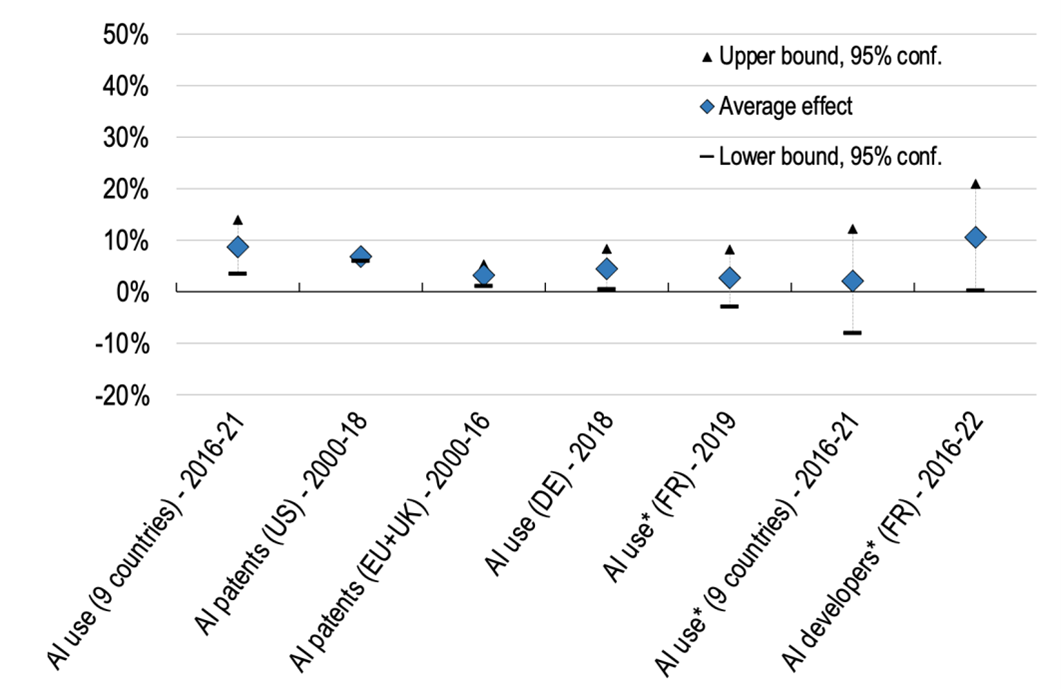

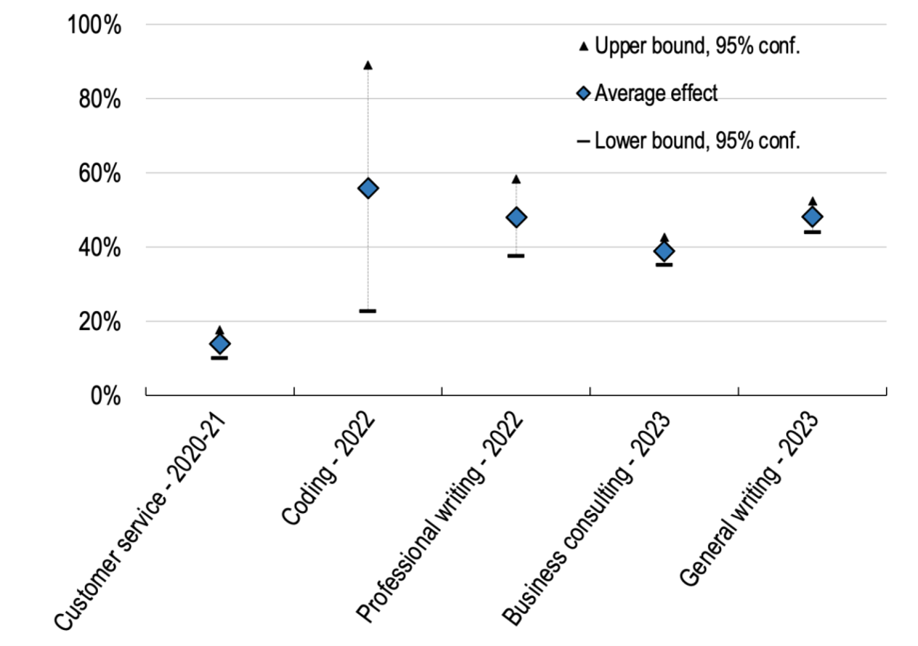

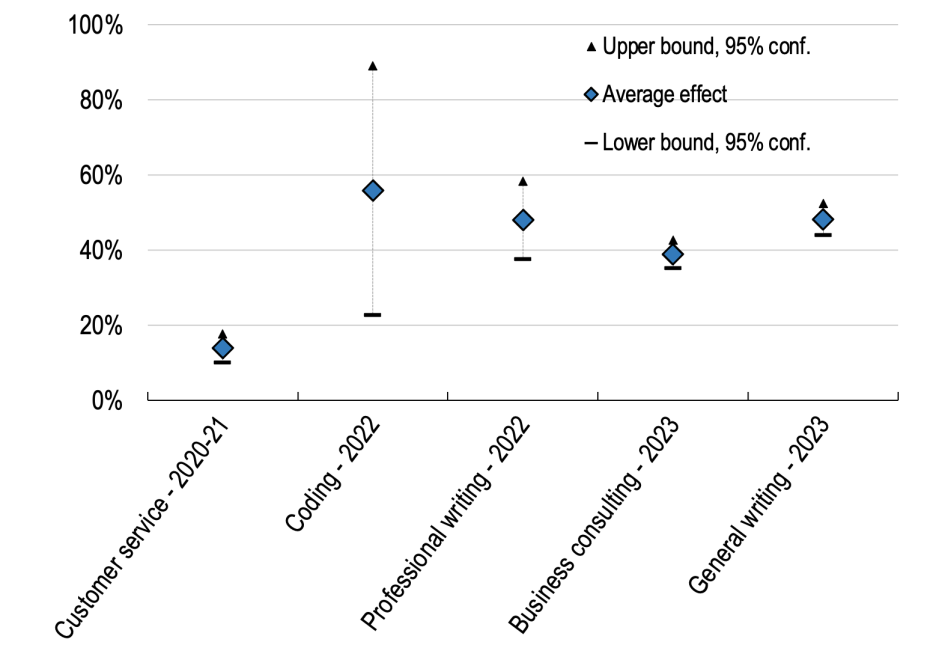

According to our overview of the fast-growing literature, initial micro-level evidence covering firms, workers, and researchers is indicative of several positive effects from using AI. First, micro-econometric studies find that the size of the gains from non-generative AI on firms’ productivity is comparable to previous digital technologies (up to 10%; see panel a of Figure 1). Second, when using more recent generative AI in various tasks – assisting in writing, computer programming, or customer service requests – the estimated performance benefits are substantially larger but vary widely (between 15 and 56%; see panel b of Figure 1) depending on the context. In particular, Brynjolfsson et al. (2023) found that AI has a much stronger impact on the performance of workers with less experience in their job. These estimates focus on specific tasks and individual-level gains. Hence, they are narrower in scope than previous firm-level studies but tend to rely more on more causal identification in experimental settings.

Figure 1 The positive relationship between AI use and productivity or worker performance: Selected estimates from the literature

- a) Non-generative AI, firm-level studies on labour productivity

- b) Generative AI, worker-level studies on performance in specific tasks

Note: In panel a, ‘AI use’ is a 0-1 dummy obtained by firm surveys, while ‘AI patents’ refers either to a 0-1 dummy for having at least one patent (US study) or to the number of patents in firms. The sample of countries underlying the studies are shown in parentheses. The year(s) of measurement is also indicated. *Controlling for other ICT technologies. For more details, see Filippucci et al. (2024).

Third, researchers believe that AI allows for faster processing of data – speeding up computations and decreasing the cost of research – and may also make new data sources and methods available, as documented by a recent survey in Nature (Van Noorden and Perkel 2023). Fourth, AI-related inventions are cited in a broader set of technological domains than non-AI inventions (Calvino et al. 2023). Finally, there are promising individual cases from specific industries: AI-predicted protein-folding gives new insights in biomedical applications; AI-assisted discoveries of new drugs help with pharmaceutical R&D; and research on designing new materials can be broadly used in manufacturing (OECD 2023).

Long-run aggregate gains are uncertain

As generative AI’s technological advances and its use are very recent, findings at the micro or industry level mainly capture the impacts on early adopters and very specific tasks, and likely indicate short-term effects. The long-run impact of AI on macro-level productivity growth will depend on the extent of its use and successful integration into business processes.

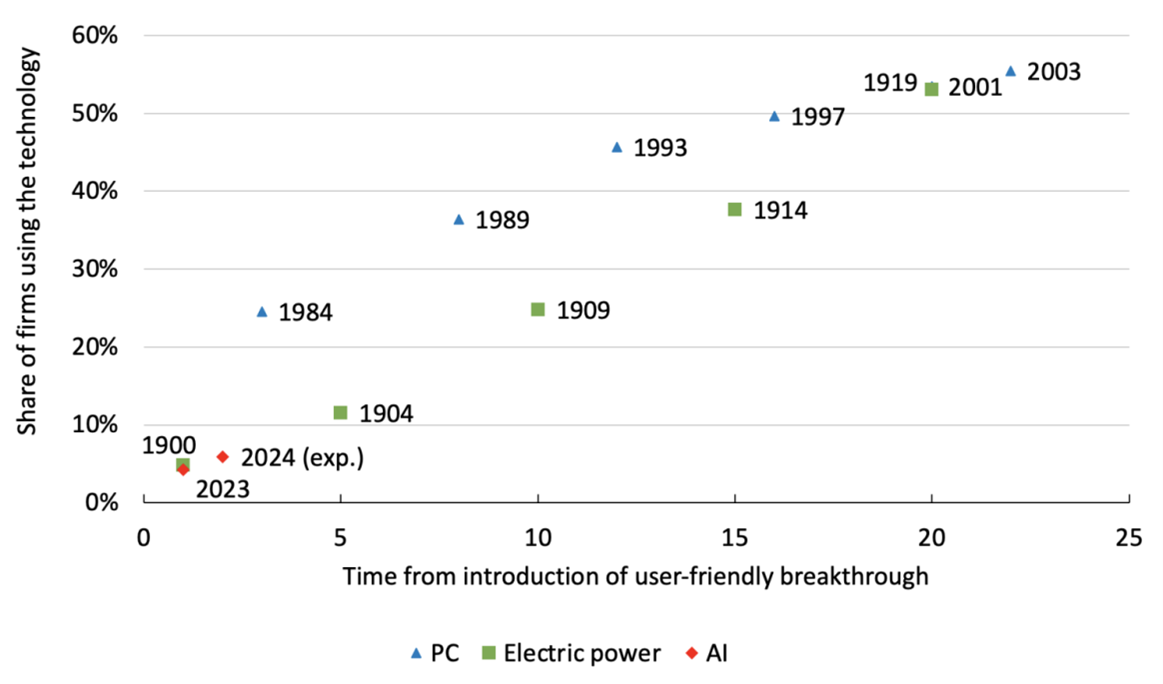

According to official representative data, the adoption of AI is still very low, with less than 5% of firms reporting the use of this technology in the US (Census Bureau 2024; see Figure 2). When put in perspective with the adoption path of previous general-purpose technologies (e.g. computers and electricity), AI has a long way to go before reaching the high adoption rates that are necessary to detect macroeconomic gains. While user-friendly AI may spread faster through the economy, the successful integration of AI systems and exploiting their full potential may still require significant complementary investments (in data, skills, reorganisations) which take time and necessitate managerial talent. Moreover, future advances in AI development – and its successful integration within business processes – will require specialised technical skills that are often concentrated within a few firms (Borgonovi et al. 2023).

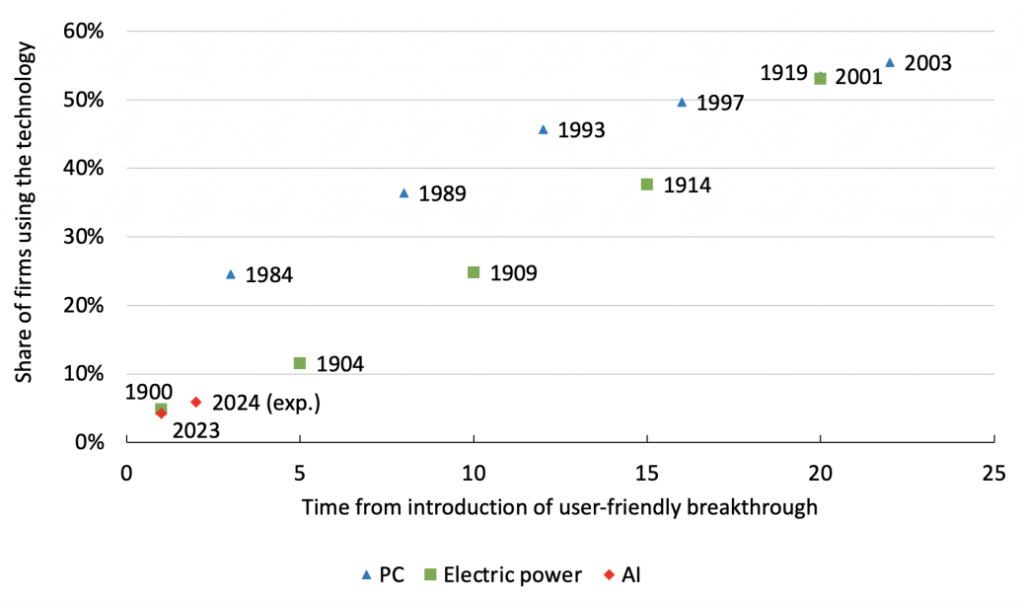

Figure 2 AI adoption is still limited compared to the spread of previous general-purpose technologies

The evolution of technology adoption in the US (as % of firms)

Note: The 2024 value for AI is the expectation (exp.) as reported by firms in the US Census Bureau survey. For more details, see the sources.

Note: The 2024 value for AI is the expectation (exp.) as reported by firms in the US Census Bureau survey. For more details, see the sources.

Source: For PC and electricity, Briggs and Kodnani (2023); for AI, US Census Bureau, Business Trends and Outlook Survey, updated 28 March 2024.

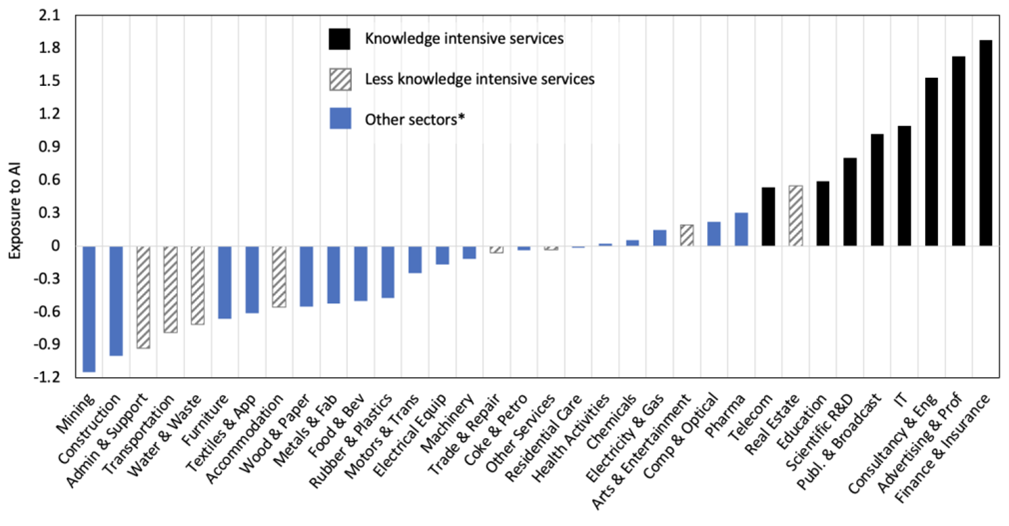

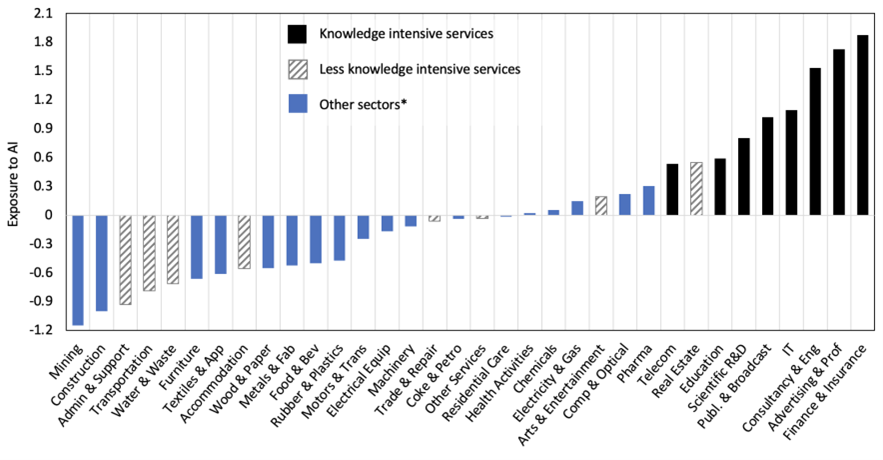

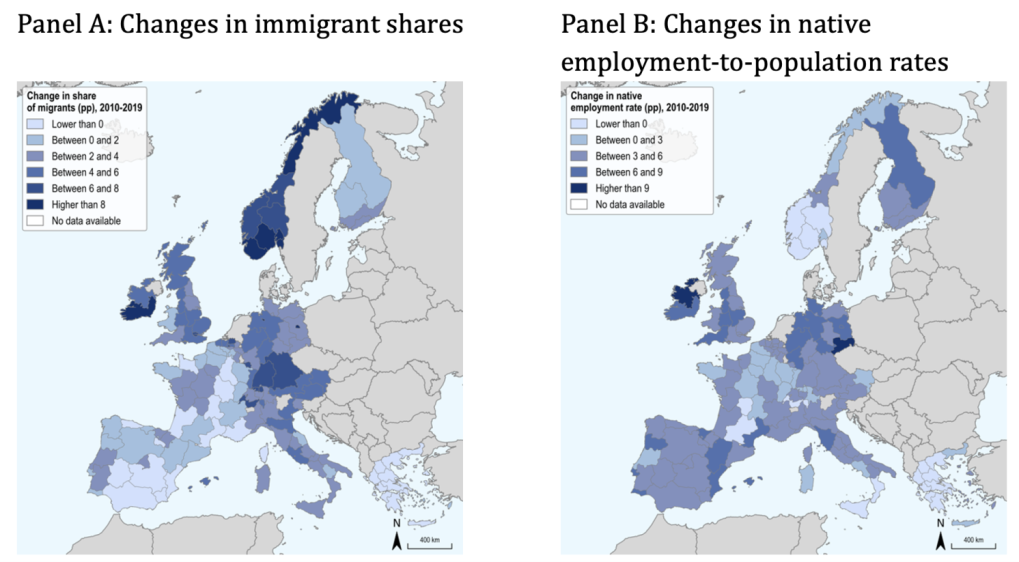

It is also an open question whether AI-driven automation will displace (reallocate) workers from heavily impacted sectors to less AI-affected activities or the human-augmenting capabilities of AI will prevail, underpinning labour demand. Currently, AI exposure varies greatly across sectors: knowledge-intensive, high-productivity activities are generally much more affected (Figure 2), with significant potential for automation in some cases (Cazzaniga et al. 2024, WEF 2023). Hence, an eventual fall in the employment shares of these sectors would act as a drag on aggregate productivity growth, resembling a new form of ‘Baumol disease’ (Aghion et al. 2019).